This article is an excerpt from ‘The Little Book of Tai Ji Quan’ by Dr Ben Morris.

Authors foreword

The pursuits and achievements of the past masters, and of their written work; what use is all of this?

It was not written to describe some esoteric babble, nor was it designed to confuse and torment those practitioners who were to come with impossible goals and aspirations. However, these men and women, through their diligent practice, teachings and writings were (presumably) not seeking to spoon feed the future generations either.

On the one, the knowledge that they transmitted was a characteristic of their time, and yet it is also highly relevant to today’s world; perhaps it is this, that is most remarkable!

In modern times it has become increasingly evident that the skills of the Tai Ji masters have been monetised. However, it is now, as it was before, redundant to say that this secret manuscript or that new DVD from the venerable Tai Ji master can provide you with any more insight than the insight that you are willing to commit to feel and experience within your own body.

The past masters were dedicated to their art form – dedicated to their ‘religion’. Who are we to presume worthy of such wisdoms?

The true treasure of this art is found in our attempts to attain the insights of these individuals – this is not through a purely academic exercise, rather through direct experiences – feel your form, feel your opponent, feel yourself. Seek what those of the past felt; temper those feelings with a diligent mind.

The content of this book however is not simply a collection of verbatim accounts. Rather it is a refinement of the knowledge that I have learned/received from my teachers and of my experiences (thus far) through testing and experimentation, coupled with a desire to sincerely communicate this to others.

“If you don’t understand something, question yourself,

If you think you understand something, question yourself,

If something you once knew is no longer known to you, question yourself,

Rest assured though, for the question is only the start”

The postures should be without defect

To aspire to perfection … but what is perfection … what is defect?

The forms, of which there are many styles and permutations, show how Tai Ji is expressed by those that teach it to you, and how those that taught your teachers expressed it. The questioning that every faithful student should engage in, is whether this is transmitted faithfully to those that teach you? What am I seeking to find from my teacher?

Ultimately a posture without defect is that which adheres to the way that the individuals body is naturally predisposed to, but here I am not talking about the way the ‘individual’ necessarily wishes (with all their biasing thoughts, beliefs, equations, preconceptions), but occurs through a consistent dedication to understanding the nature of mankind. Subsequently defect can be expressed as a movement away from natural postures.

The syllabus of Tai Ji Quan was honed over many generations, and whilst it can be easily distorted over one generation, there are many guiding principles that follow this natural disposition of the body.

Some key physical guidelines:

- Head upright, spine upright and as if suspended from above

- Shoulders relaxed, elbows relaxed – neither fully open, nor fully closed

- Chest relaxed and back rounded naturally

- Spine straight and relaxed from the top to the bottom vertebrae

Thighs relaxed (primed for action), knees bent (but not crouched)

Ankles light, but firm and assured

Feet planted firmly to the ground – as we ‘swim’ through the air, our feet remind us that we are never far from safety

As mentioned in preceding sections, the marriage of body, mind and spirit is essential for human development. So is this marriage important for the achievement of postures ‘without defect’. In seeking out and rectifying defect, look deep into your physical postures, your mental state and the spirit of your conduct. The resolution of the latter two may necessarily be a harder task! Since these factors are interconnected one will always bare some influence on another.

“Train to make your body strong, ultimately train to find your bodies’ true nature”

Your teacher is your guide, if what they practice works in your eyes, then learn from them. Have faith in your teacher and have faith in your judgement of them.

… without hollows or projections from the proper alignment …

This passage notes that whilst ‘hollows or projections’ may occur, the form should ultimately be trained to avoid them. Mistakes in the form however are inevitable (which means don’t over think upon them). The remedy for such error can be found through proper alignment. Proper alignment can be found through cultivating a strong centre, in all movements, in all parts of the body, and when those parts come together to form the whole.

- A hollow is an excess of retreating often manifest by a deficiency in ward off energy (Peng jin) or a misunderstanding of roll back energy (Lu Jin)

- A projection is the result of separation between the whole and a part of its whole. It may be a technique that relies upon the overemphasis of a specific part of the body. Such a technique is necessarily weaker than its ‘whole’ technique counterpart.

“Imperfections should be smoothed out over time, as water smooth’s rock; quick results are not the guiding principle here”

Under a magnifying glass

Often in combat these ‘hollows or projections’ can be magnified by the actions of an assailant – essentially compounding the situation! Since hollows and projections represent weaknesses, the opponent will seek to magnify them to their good end. A key in such instances is the ability to return to your training … to return to your centre.

Through the identification of ‘correct’ alignment, the practitioner develops ‘safe zones’ where they know their range of motion can be better controlled by themselves and less well exploited by another. In Tai Ji Quan central equilibrium (Zhong ding) can be viewed as such a position (although merely a conceptual idea at first), it is a place where the practitioner can comfortably stage a number of options to steer a better course of action. This is why any form necessarily begins with a preparation sequence (e.g., heaven & earth, seal knot) where there is acute focus placed upon balancing the centre.

It may be useful to ask yourself some of the following questions when formulating your ‘safe zones’, if you disagree with such an approach, then how truly safe is your form, practice and martial art?

- How much force can I realistically ward off?

Have I trained this skill?

What is the range of my punch? - How powerfully can I punch?

Can my fist project power and how have I trained this?

Can my fist project force and how have I trained this? - Am I comfortable fighting on the ground? Do I have methods to get off the ground?

More options provide better chances of survival. Although I may not want to end up on the ground, I need to have a plan if this occurs - If correct timing and position are not achieved …

Timing

Timing in offence should be such that a strike is made when the potential for effect will be maximised. Timing in defence should be that the practitioner is either not there when their opponent strikes or they present a strong defence capable of managing the incoming force (the intercept contains strong Peng jing). Managing force can be either through neutralising (to make the attack disappear), redirecting (to move the force from its intended direction) or borrowing (taking the energy of the incoming force and using it, reapplying the force back into the opponent).

Position

Correct positioning can be achieved by ‘moulding’ your movements with that of your opponent. This does not mean to become the puppet of your opponent, but rather present no openings for the opponent to enter, and to enter into any opening that the opponent presents. Ting Jing (or the skill of listening) allows the individual to identify where the opponent is, and where they intend to go. With this knowledge, the practitioner can identify neutralising positions and advantageous positions where their opponent cannot reach them.

Positioning can also refer to a matching of timing with your opponent. Once this timing is achieved with ease, a change in tempo can provide additional openings that allow dominance of the situation. Most martial arts are dependent upon this appreciation of timing. Tai Ji Quan is no different!

… the body will become disordered …

Failure to capture the two preceding characteristics (timing and position) is to fail to acquire the pinnacle of movement, which is to realise the efficient use of your energy. If the aspects of correct timing and position are not trained then the individual becomes vulnerable to being their opponents ‘puppet’ – their survival in such a scenario is thus down to their opponents failure, and not their successful ambition.

When I am under the control of another, my body may become open to the opportunity of the opponent, and my thoughts (‘Yi’) may become disorganised and catatonic. The ability to recover may be compounded by a downward spiral of physical pain, mental negativity and diminishing spirit.

The great professional fighters throughout history not only possessed immense strength of body, mind and spirit, but were also able to recover when these attributes became ‘disordered’. Certainly having a disordered body is no route to success. There are several ways to foster this ability to recovery; principally this would be through applying yourself within environments

Alternating the force of pulling and pushing severs an opponent’s root so that they can be defeated quickly and certainly

‘Pulling and pushing’ is not only done on arms, shoulders, chest, but can be done elsewhere in the body. If I can unify my opponent in an unfavourable way his ‘one unit’ can be used against him, his root when severed will certainly lead to his fall.

If through pushing and pulling I can remove the flexibility of my opponent’s body I can strike with strong effect. If I can make my opponent ‘freeze’ he will be unable to complete his plans, unable to apply his skills and will necessarily lose. Correct application of angles of attack and priming my opponent to behave in certain ways allows this to happen easiest. Intimidation is a form of pushing and pulling, it produces the same effect in the form of a reaction (e.g., fear), this moves the recipient from their psychological root and unbalances them.

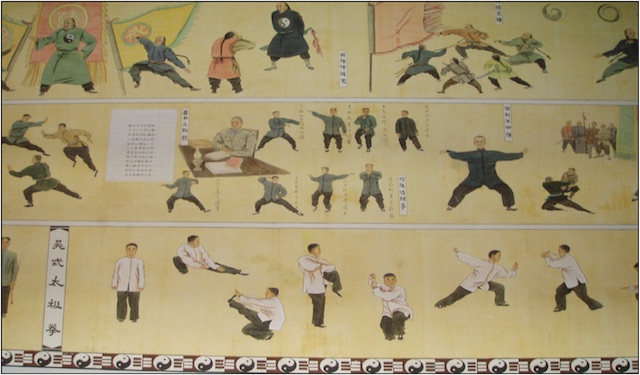

Above and below fresco’ from Chenjiagou, taken 2008

The whole body should be threaded together through every joint without the slightest break

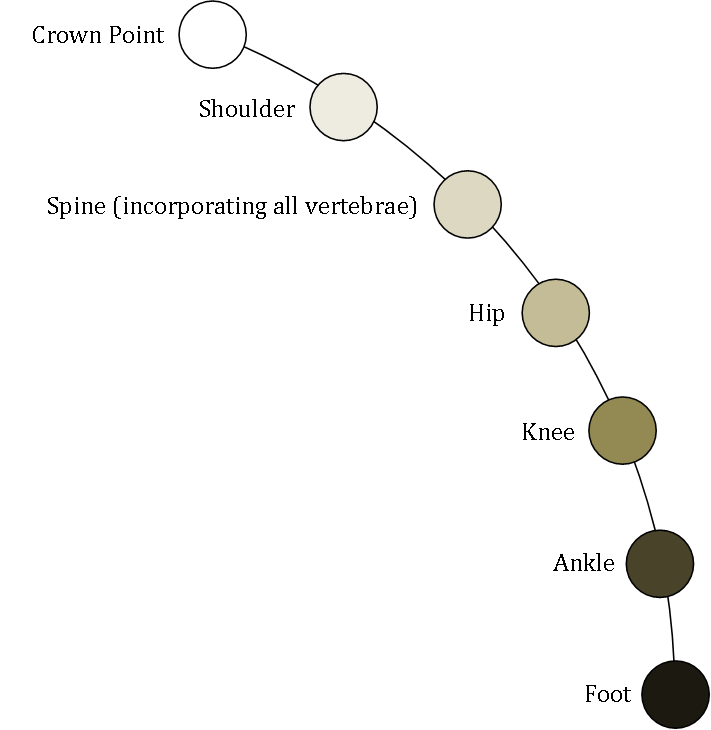

The threading of the body from joint to joint means that there are no parts of the body that are neglected during movement. The diagram below is by no means comprehensive, but gives an impression of a body threaded together.

“Connection of movement is cultivated in the form and tested under confrontation”

When joints are in vulnerable positions they become susceptible to breaking, when they try to move from sub optimal positions they are

weaker and less efficient. When the body stops it does so as a result of the joints stopping. A limb that continues to move with purpose is hard to capture, a ‘whole’ body even harder.

Basics of Tai Chi

Some useful resources

Here are some useful resources that the author has found helpful up to the writing of this book.

Websites of some trusted organisations

www.yiheyuan.co.uk & www.taichileeds.co.uk – School of Masters Colin and Gaynel Hamilton

www.realtaichiuk.com – a no nonsense resource for Tai Ji Quan

www.7starstjq.co.uk – School of Master Bob Lowey

www.zhong-ding.com – School of Master Nigel Sutton

DVD’s

Tai Chi Chuan: The Cheng Man Ching Form, by Master Hamilton

Tai Chi Chuan: Yang Style Broadsword, by Master Hamilton

Tai Chi Chuan: The Yang Style Long Form, by Master Hamilton

Tai Chi Chuan: Wu Dang San Feng Gun, by Master Hamilton

Some suggested reading

Although not a complete reading list, here are some texts that have proven useful to the author.

Tai Ji Quan

Gilligan, P. (2010). What is ‘Tai Chi?’. Singing Dragon: London

Liao, W. (1990). Tai Chi Classics. Shambhala Classics: Massachusetts

Lien-Ying, K. and Guttman (1994). The T’ai Chi Boxing Chronicle. North Atlantic Books: California

Sutton, N. (1998). Applied Tai Chi Chuan, 2nd edition. A & C Black: London

Swaim, L. (2005). Yang Chengfu: The Essence and Applications of Taijiquan. Blue Snake Books: California

Bjm Story Series (short stories inspired by the far east)

The Story of Yin and Yang

The Five Element Sword

The Legend of Zhong Ding

The Animal Warrior Scroll

The Temple of the Four Directions

Other interest

Brahm, A. (2005). Who Ordered this Truckload of Dung?: inspiring stories for welcoming life’s difficulties. Wisdom Publications: Boston

Miller, R. (2008). Meditations on Violence: a comparison of Martial Arts Training and Real World Violence. YMAA Publication Center: Massachusetts

Powell, G. (2009). Waking Dragons: a martial artist faces his ultimate test. Summersdale Publishers: West Sussex

Sheridan, S. (2009). A Fighters Heart: one man’s journey through the world of fighting. Atlantic Books: London

Twigger, R. (1997). Angry White Pyjamas: a normal bloke becomes a deadly weapon. Orion books: London

Author: Dr Ben Morris

Images: Dr Ben Morris