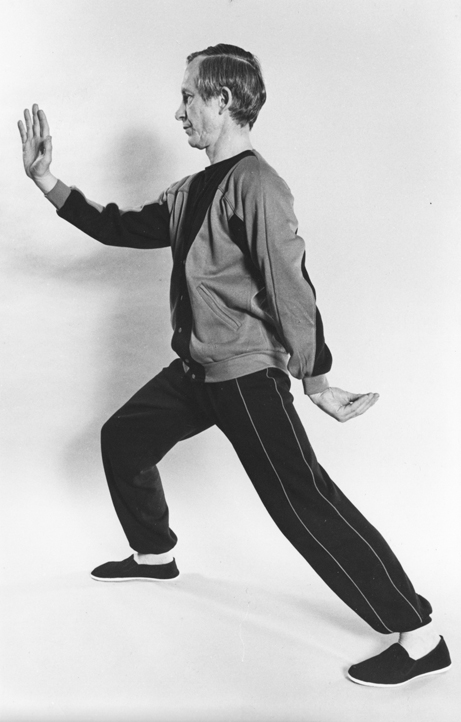

Paul Crompton has taught Tai Chi for over forty years and is internationally recognised as a teacher as well as the writer of authoritative books on Tai Chi and Martial Arts. His classic introduction to the short form remains an essential primer for all newcomers as well as an authentic and accurate study of the origins and purpose of this ancient Chinese system.

This interview was by Ronnie Robinson, Editor or Tai Chi Chuan and Oriental Arts magazine.

When did you start learning tai chi and why?

I started learning in 1968. I had always been doing martial arts, beginning with boxing at primary school, judo in my teens and then later on karate, kung fu and aikido. I was stimulated to begin judo because my parents sometimes talked about James Cagney who appeared in a film called “G-Men” (FBI) where he had easily thrown a man much bigger than himself. As a youngster this made a big impression on me. I also expected to find a spiritual dimension of Zen Buddhism in this art but I was disappointed.

What do you think it was about tai chi that caused you to specialise in it, as opposed to the many other disciplines you studied?

I found that the “meditation in movement” aspect attracted me. Also I had been learning and studying the Movements and Sacred Dances brought to the West by Georges Gurdjieff. One of the important factors in this is exactness, and also there is sensitivity to movement, and many other things. This linked, in my experience, with Tai Chi. How and why it did so is impossible to explain in an interview such as this. I am not being evasive. It is a matter of experience.

Who were your first and most influential teachers?

My first teacher was a pupil of T. T. Liang’s from New York. I worked privately with him for a year learning the Yang Style Long Form for a year.

My second teacher was Teresa Yang a Wu stylist who studies with her father, a nerve specialist from Hong Kong. Again I studied privately to study the Wu form, which is more or less the equivalent of the Yang Long Form.

Later, through my martial arts magazine I met Master Un Ho Bun whose specialties were Praying Mantis and Pak Mei (White Eyebrow) kung fu. He had learned Yang style in Hong Kong from a Yang family member. Though tai chi was not his specialty he moved very, very well and his hand movements were truly memorable. From him I learned Yang style with a very low stance, which was something you rarely saw. He also took me through basic Praying Mantis, Mantis staff and Pak Mei, but I would never claim any real knowledge of these systems. Some of the movements have stayed with me and I still maintain great affection for Master Un.

I learned push hands from Dr Ji, a Hong Kong herbalist living in London. His forte was very soft push hands. I introduced Bruce Frantzis to him to push hands, and I believe Frantzis was impressed by his softness.

In the 1980’s I studied Chen style for a while with Ji Jian Cheng, but I would not regard myself as a true practitioner of the style. Certain moves appealed to me and I still do them. For example the Chen Wave Hands is very attractive to do. Pounding the Mortar is also a delight to do. The change from soft to hard and back again is a great challenge, which is not found in other styles.

How did you find teachers at that time, I can’t imagine it was easy?

I had been studying the Alexander system with Mrs. Marjorie Barlowe, the niece of F. M. Alexander, the founder. She invited me to a demonstration of Tai Chi by the famous Gerda Geddes, given to the Alexander Foundation in Holland House, London. Views on her Tai Chi vary, I know, but I was sufficiently impressed to pursue it. One of the Alexander teachers was from the U.S.A. and a man whom he knew had just arrived from New York. It was my future teacher.

Did you have much contact with the few other practitioners in the early days, I’m thinking in particular of people like Rose Li, Gerda Geddes, John Kells or any other early pioneers?

I met Rose Lee only once and was impressed by her. Gerda Geddes I saw at the demonstration I mentioned but I did not study with her. John Kells began his Tai Chi with the same man as I had done. Later on through Danny Connor I met Bruce Frantzis. In those days he was lightly built, agile and fast. But he was too full of beans for me! Later he had a dreadful motor accident, was badly injured, and then gradually came back to health. But I guess that the accident caused his physique to change and as you know he put on a lot of weight. I met him a few times when he taught around the south east of England. He showed me a few things but I was not a pupil of his.

Remember that by this time I had had a lot of experience of martial arts but also of the other things I have spoken about. One’s body has an intrinsic intelligence and sensitivity and I knew that mine had developed considerably over the years.

With your first teacher, were there many other students or did you mainly work on a one-to-one basis with them?

With my first teacher and with my second, Teresa Yang, it was on a one to one basis. It was only when I took up Push Hands that I began to go to classes.

How were you taught, were you shown one or two moves, left to practice and then corrected or did you spend a lot of time working with preliminary exercises?

I just slogged through the Long Form, one or two postures at a time, corrections, adjustments, corrections, adjustments. With Teresa I followed her around London. I would find out where she was at a particular time and just turn up, sometimes at her house, sometimes mine, sometimes after some meeting she had been attending. It was a very traditional experience. I had to make all the effort to find her but when I did she taught me clearly. This was again a few postures per week over approximately a year. Finally she married an Englishman, went back to Hong Kong and then on to Hawaii I believe.

You mention Bruce Frantzis, how did you meet him? Was there a ‘network’ of these few people who were training at that time and was it common for you to share or discuss skills?

As I said, I met Bruce through Danny Connor. Bruce was having a difficult time. I paid him for a week of private lessons. We actually ended up one day having a scrap in my sitting room, which finished up as an all in wrestling match beside the bookcase. This is a fact but readers should not take it too seriously, or make a meal out of it. Bruce told me that I had a lot of “sinew strength” which I already knew. I used to fight and arm wrestle with my father, in my teens. He was a very strong man and had been a motor mechanic in his youth. There were no machines to do the work in those days. You did it with your own muscles and determination. Chewed nails and spat rust!!! He later became a car salesman but he had muscles on his muscles. So I did have, and still do have at my age, strong tendons. As I said, I did know Master Un Ho Bun, and a few Chinese, but in the main in the time before Danny came back with his knowledge of Tai Chi there had been no network to speak of. Later there was.

So you tried different styles before settling with Yang Style?

Through various people I worked on different aspects of the systems I trained on. I did some training on Sun Lutang’s style of tai chi which is completely different from all the other styles. It is quicker, the movements are different and it is designed for speed and fluidity and getting out of difficult situations. Sun was skilled in Pakua (Bagua) and Hsing-I (Xingyi). He was also one of the most learned of all Chinese martial artists.

What aspects of tai chi did you learn initially?

From my first teacher I learned exactness. I learned one or two postures in each lesson, going over them and revising them. He was a stickler for exactness and I was quite happy to go along with what he said.

When and where did you first start teaching?

There was an Australian man who knew I was studying tai chi, his name was Barry Levy. He pestered me to teach him but I felt I was not ready to as my ability was not so good. This must have been four or five years after I had started. Anyway he wouldn’t give up and I felt that his persistence ought to have some reward. Bear in mind I was perhaps one of the first non-Chinese to be doing tai chi in London in those days. Almost no one had the faintest idea what it was.

After you started teaching Barry did you open up classes or did you expand your teaching as an addendum to perhaps teaching other disciplines?

Barry brought his girlfriend to the class, and a male friend, the word got around and pretty soon I did have regular classes.

What was the background of your first students and what attracted them to tai chi?

My first students were not connected with martial arts at all. I am not sure why they wanted to learn. Sorry to be unhelpful but it was never clear to me. They just wanted to learn!

So if your early students weren’t from a martial background did you focus primarily on non-martial aspects of the art?

At first yes, but as I said before, martial people were attracted. There was a much younger man called Sean Dervan and then one or two of his brothers. They were bouncers in their spare time, or if you prefer, doormen and bodyguards. A judo man came, and a student of ninjutsu. Then I met Mantak Chia, the qigong teacher. He came to London and I gave him a little publicity in KOA magazine. I went on a seminar with him. Later a pupil of mine and I went to Boston in the U.S.A. to study Qigong with him.

Always remember, when I am talking about those days, Chinese Kung fu and Chinese Qigong (Chi Kung) were hardly known in the West. There was opposition to opening up these subjects to non-Chinese. Mantak Chia asked me to represent him in the U.K. and promote and teach Qigong over here. I declined his offer. We kept in touch for a while but then drifted because we had nothing to say to one another. There were no hard feelings, no fallings out, nothing like that. We just went our separate ways.

His chief pupils at the time were very impressed with my ability, and said so, openly. I am just telling you the facts, no boasting. Mantak Chia himself asked in front of all his pupils for my views and opinion on what he was teaching. People in England heard about this and came to learn from me, so you can add them to my pupil list. In the main though, people expected miracles from qigong. There is, and was, so much rubbish written about it. Of course it can be beneficial and of course there can be surprising results, but this is true of other systems that have nothing to do with China.

What were the key aspects of your teaching in the early stages and how did they change as the years progressed?

Like my first teacher I emphasized exactness. I wouldn’t allow the slightest deviation in posture – foot position, foot angle, torso uprightness, hand shape and position, head position, direction of gaze, etc. Barry Levy eventually asked for permission to teach. He had been asked to start a class at Goldsmith’s college in east London. Gradually we lost touch, and some ten to fifteen years later he came to see me and to a class. He was completely flabbergasted that things had changed, i.e. I was not doing tai chi in the same way. When he showed me what he had been doing all those years it was exactly the same as when had learned from me. That’s fidelity for you… But he had not moved on, at least not in the way he did tai chi externally. This was a most striking thing for me to see.

Given the precision of your teaching style were students happy to stick with it or was it like it has always been, a high drop-out ratio?

In the main, in those days, people stayed with me. Today, people often expect results almost overnight. It is an interesting question about the times in which we live. As years passed though, my emphasis on precision changed. Nowadays I do not emphasise it initially at all. I have developed a completely new approach to teaching. With this approach, people can be doing Tai Chi quite reasonably after about twenty minutes of trying, in my classes. Tai Chi needed a complete re-think and I have gradually given it one, to my own satisfaction. I am not trying to change anyone else’s views of course.

How many people were teaching in the UK in the early days?

Just me! No I am joking. My own teacher moved abroad and one or two of his pupils also started teaching. I can only say very, very few.

How did you work to promote tai chi in the UK?

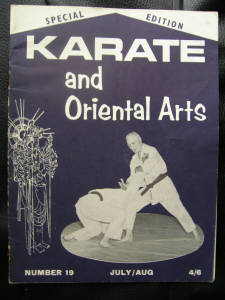

Well I started the first martial arts magazine in the U.K., Karate & Oriental Arts, in 1966, and I ran it for 22 years then closed it down. I had had enough. I used to feature tai chi in the magazine, and mention books and so forth.

I conducted courses and also I taught at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, the Royal College of Music, the prestigious Omega Centre in Upstate New York,

David Lloyd Fitness Centres, two karate clubs in Canada and had my own classes at the Lilley Road Fitness Centre in London. Later I ran classes in my garden and a small building at the bottom of the garden. With these classes we explored the tougher side of Push Hands, in other words quick, effective moves, the martial aspect. Prior to this we had done very soft push hands, reminiscent of Dr. Ji and by association T. T. Liang and Cheng Man-Ch’ing. I am not that tall and lightly built, but I managed to send some really hefty chaps flying. My pupils questioned this but later when four of them went to Singapore to see tai chi there they were really put to the test by tai chi men there and were grateful that they had been through this tougher process with me.

As editor of this journal I have a particular interest in how you gathered material for yours. I know you have to be pro-active to get quality material but surely it was more difficult back then with fewer practitioners, less direct contact with China etc.

Certain types of material were scarce, for instance Tai Chi, Hsing-I and Pakua, also Qigong, but Wing Chun people were becoming very anxious for publicity because of the massive Bruce Lee connection. There was not really a shortage of material, but rather a shortage of detailed material. Aikido sensei for instance were also keen to promote their art so they were mostly forthcoming.

So you were involved in teaching push hands, applications etc. How did you work to teach these aspects?

Push Hands is a controversial subject. But it is so simply because people argue over words. Say there are three sides to Push Hands: very soft, strong but according to certain conventions, and the relatively new ‘freestyle’ which is of course not freestyle because there are rules and a “play area”. You simply have to decide which one you are talking about and the controversy disappears.

In your teaching of push hands did you start from a point of precision (as you did with teaching hand forms), getting the stance, structure and focus in the right places or did you work more on teaching sensitivity, awareness etc. I’m interested to know how this aspect was both taught and practised in the early days and how students received and developed this information. Still today there are many views and interpretations in this work and I wonder if a historical insight to the early teachings are helpful. Even If not, I’m sure they’re still of great interest.

You know, I am just one person, but there were few of us then, even so don’t take what I say as true of everyone. Mainly I stressed relaxation and softness. Later, I began to realise that there was a lot of stupid talk about the power of Tai Chi and began to apply a much more martial approach, which, as in the case of my pupils who went to Singapore, proved a good thing. Bear in mind that Tai Chi, soft or martial, has certain limits or “rules” if you like, and this can produce tension, competitiveness and misunderstandings. A strong, able martial artist, if you make him stand in one spot and keep his balance when pushed, he will find it difficult. But the fact is that he will never in his life have to do this, except in the Tai chi fixed step context. So the mechanics of fixed step Tai chi are completely artificial. They are interesting, they are testing, they are enjoyable, they are instructive…. etc., etc., etc. As I said elsewhere in this interview, you pay your money as it were and you take your choice. You elect for a certain context and everything else flows from that.

Did you feel it important to teach the philosophical aspects of the art?

The philosophy of the art is closer to Taoism than anything else. The so to speak ‘purer’ or earlier Taoism is a matter of immediate, direct experience. There are no words. “He who speaks does not know. He who knows does not speak.” But for western people and for eastern people educated and raised in a western style such an approach is more than most of them can bear. They have to have an explanation. So I would tell pupils just to read the classics and leave it at that. I close all my classes with meditation, which I have been doing for nearly sixty years now.

The meditation side of my life is something I have never written or spoken about directly. People in the martial arts world who know me do not know about that side of my life.

Can you tell me a little about your approach to the meditative aspects, do you encourage them to stand, or sit quietly, do you direct them to their breathing or do you talk through a particular sequential process?

We do all those approaches, and more. From one point of view all these things can begin at once. From another they should be approached very gradually. The main point is that the teacher, (if that is the right name), should be very well trained and have the state of being to be able to pass on what he or she has learned. Repeating instructions like a parrot is worse than useless. I studied one approach to meditation for over ten years, yes, ten years, before the teacher gave me permission to begin passing it on. And I accepted it. If you look around today there are people who are unstable, and they are passing on teachings about man’s inner world. But this mainly boils down either to a dreamy altruism or getting cash.

Did you teach the historical aspects of the art and if so did your views on the history of tai chi change as more information became available?

Once again I referred pupils to books written by people who knew more than I did. Robert Smith is one of my favourite writers on this type of subject. With him you get no humbug. And he writes with such affection and consideration. Some people criticise and attack him but I don’t see why. They are small-minded and narrow hearted.

There is no room for negative emotions in tai chi. All your attention should be on sensing the body, relaxing the body, letting gravity work and direct, letting the air come in and go out. Who created your body? Not you. Who keeps it alive? Not you. Who will finally bring it to an end? Not you. So a little clear thought like that puts you in your place.

What do you feel is the ultimate purpose of tai chi?

Tai Chi itself does not have a purpose. Tai chi is a teaching. It’s like the Sabbath in the Bible. The Sabbath was made for Man, not Man for the Sabbath. Tai chi can show us something about ourselves, and the planet on which we were born and live. It can re-introduce us to our bodies, to the earth’s atmosphere, to the universal existence of gravity, which holds the whole universe in place, to the presence of our fellow human beings. In these troubled times it can help us to slow down and reduce stress, to coin a phrase!

So do you feel that the ‘listening’ aspect of the art is an integral part of training?

Listening is a very big part, listening with ears, with hands, with skin, with every available part of oneself.

How has tai chi served you personally over the years?

Tai chi has helped me in the ways outlined above. I especially appreciate its slowness and the totally different experience, which this slowness brings. One thinks at times about the possibility of thinking slowly and carefully too.

What do you feel comes out of the ‘slowness’ that perhaps is difficult to access without it?

Time and space…

What are your views on the competition aspects of tai chi?

All this stuff appeared when I was getting older you know. My view is that if you want to fight you should do boxing, judo, jujutsu or wrestling. If you are very tough and, in my view unwise, you can try all-in wrestling, but that could be fatal. I learned fixed-step push hands first, then with stepping, and then a type of freestyle. But I always found it unsatisfactory. Fixed step is interesting but so totally artificial. It can develop skill, but mainly the skill of doing pushing without moving the feet. We have all seen Chinese experts getting hit with sledgehammers and walking away, but what is the purpose of that? If the same person were hit on the head with a hammer when he wasn’t ready, it would kill him like anyone else.

Push hands can be enjoyable, but for me it raises the whole question of martial arts and martial fighting. In martial arts we explore what is possible, given certain very special conditions. We do not, in the main, explore what happens on the street, on the football terraces, in the pub, and so forth. In a martial arts competition of any type the conditions are perfect, with clear rules and etiquette, and so forth. This is all artificial, more like a game.

When I did Aikido I was disappointed to watch competitions where one person attacks with a rubber knife whilst an opponent has to defend and throw his attacker. What I saw was a shambles, a mess, just a free for all, with little trace of Aikido technique. This was because the training conditions were so artificial. So martial arts are a type of game, detached from real life circumstances.

It is the same with solo form competition. Tai chi in competition is one thing but tai chi done for oneself, and for one’s own understanding and improvement, is something else. They are not the same thing and this should be made very clear.

To me, to come out and do a form and have a bunch of people giving me marks, and deducting marks, is just nonsense, rubbish. I do tai chi for myself. I am not interested in getting marks. Marking people is so subjective. In the world of tai chi associations and tai chi promotions and so forth it is fine. If people want to do that then it is a free country. I won’t try to stop them, and they won’t try to make me.

Do you have an opinion on how tai chi has changed over the years with respect to modern forms being introduced and in comparison to the traditional systems?

We all followed the progress, if that is the right word, of Communism in China, and saw the complete about face they made. First they outlawed martial arts and then they welcomed them back with open arms. Did tourism, trade and dollars have anything to do with it? You decide. Politics and cash have played a big part in this subject. Many early martial artists were illiterate and poor, eking out a living teaching and showing their arts. There were exceptions of course, and if you gained a reputation you gained the money that came with it. The modern Chinese introduced training programmes, with scaled difficulty in the forms which was applied as part of an educational system. They had millions of people to deal with so some kind of order, something to be followed, seemed like a good idea.

I believe that in both China and Japan, martial skill was a type of job. If you had the skill, you could, like a modern day mercenary, be employed as a bodyguard and similar. This shows that changes are mainly brought about by political or financial influence. There are no old style samurai in Japan today, because they are not useful any more. There may be some business samurai but that is something else.

So one can be practical about the question. It is no use kicking against the pricks. (This is a biblical expression by the way.) I just bow to the inevitable, like the Tao advises. That being said, it is interesting to look at some of the modern forms. For instance towards the end of the 24 Step Beijing Form there is this movement where you hook back with a crane’s beak hand position, at the side of your buttock or hip. Have you ever seen that in a tai chi form? I haven’t. Where does it come from, someone tell me?

In the 48 Forms there is this opening sequence with very big movements, what for? Also in the 48 step form there is that circling action when you do Play Guitar. Personally I admire Madam Bow Sim Mark for the Combined Form. There are movements in that which you do not see anywhere else. It is such a pleasure trying to do that Form well. It is like being given a new book to read on a subject that really interests you, but you get new and refreshing movements instead of paragraphs.

Can you provide an outline of your training programme over the years detailing which aspects of tai chi, qigong and other Chinese Internal Arts you may have trained in?

I could write a book about that, believe me. But let me tell you about something which will interest or please or irritate your readers. It goes like this. I never do more than one posture or move on the same leg. For instance, when you do the first Single Whip in the Cheng Man-Ch’ing form or the Long Form you have probably been taught to keep weight on the left leg, moving from Single Whip to Lift Hands without shifting weight. The knee does not like it. It is not practical in a muscular or balance sense, and as I said your knee does not like that at all. What I do is shift weight on to the right leg, turn the left foot in about 45 degrees, then move weight on to the left leg and do Lift Hands. So wherever this keeping weight on one leg for two successive movements occurs you should shift weight first. There are also some more subtle occasions in the Form when you do this, so slightly that no one can see you are doing it, but your body feels it and is happy about it. I know all the arguments against it and I do not agree with them. I trust what my body says. Now in the 1980’s I had a Chinese teacher whose own teacher was a pupil of Yang Cheng Fu. He gave a demo of the Long Form and he did the weight shifting exactly the same as I did it. I need hardly tell you that I felt very happy when I saw this because it kind of reassured me that I had made a good choice in changing what I did.

Another thing I do sometimes in the Form or in Qigong. I let my body feel very, very light, almost as though it had no weight at all. There are many things I could speak about. I am almost 73 years old now. Over the years I have learned Qigong and different aspects of meditation, and have developed methods of my own. You know the legend of Chang San Feng and how he learned tai chi in a dream. I thought, years ago, that it was not exactly a dream, but rather it came to him, if the legend is true, when he was in deep meditation of some kind. Not a dream as we think of it. So if you can go deeply enough into yourself, your body and intuition ‘teach’ you, if you are sensitive enough to listen and hear and interpret what you have heard sufficiently well to carry it out.

Can you outline the benefits of the various aspects of tai chi, i.e. hand form, push hands, applications, weapons etc.

Speaking briefly about this immense subject I would say that they give you a repertoire of movement. They show you possibilities, which you might never see on your own. They open up the body and use the muscles in an inspiring way. Everyone who is interested in tai chi has experienced the pleasure of learning a new movement or having light shed on an old movement.

How do you feel about the way tai chi is taught and practiced today?

I used to concern myself about that kind of question but now I don’t. What people do is their business. The world is going down the tubes today in many respects. At the same time there are signs of small creative moves being made, the recapturing of what is fine and true in humanity. But one aspect of this question is that everyone wants things fast. They are not prepared to work and let things sink in, gradually, to let themselves adapt in a law conformable fashion. I know for a fact that some people are “teaching tai chi” who are barely able to stand up. The main thing is that any tai chi teacher must learn to adapt vis-a-vis pupils and classes. He or she may sometimes be obliged to go against what their convictions tell them. But the point here is that having gone down a particular route to suit pupils for some reason, then find a way to bring them around to what you want, so that they hardly notice it happening. This needs patience.

This reminds me a little of a talk | once gave entitled, “A Public Perception of Tai Chi and How to Exploit it,” which centred around people’s ideas of what they thought tai chi was, why they decided to study it and what we could do to meet these ideas without necessarily compromising the essential elements of the art. It’s about being adaptable within a framework of strength and clarity. Is that what you’re referring to?

You need to be clear. If you are teaching tai chi to help people in some way, and also to earn a pound or two, you have to adopt any means you can, within limits of course. You need to “teach from afar” as Gurdjieff put it, sometimes. In other words, you cannot always go straight to the point of what you want, you have to sugar the pill for instance, or begin from a completely different direction. Not many people can take an instruction directly: relax your shoulders, for instance.

But if you show them how the muscles in the shoulder area work and get them to feel it with their hands then they begin to understand it better.

Do you have any hopes for the future of tai chi?

Whatever is happening now, good or bad, if it becomes part of an evolutionary spiral which humanity as a whole desperately needs then its future looks positive.

For the last ten years I have been teaching older people, mainly for charities around London. Ages vary from 55 to 100 years old. I don’t just teach tai chi in the class but bring in other things. What older people need are: mobility, circulation and wake up the brain. Tai chi can help with those but you need other things to enable older people to do it. I have a programme which my pupils really like a lot. Probably others have found the same thing. So I hope that all the traditional forms remain, and at the same time that tai chi is a springboard for the development of other disciplines. Any tai chi teacher should be able to bring about certain things in himself and others: relaxation, mobility, a kind of alertness and silence, inner silence.