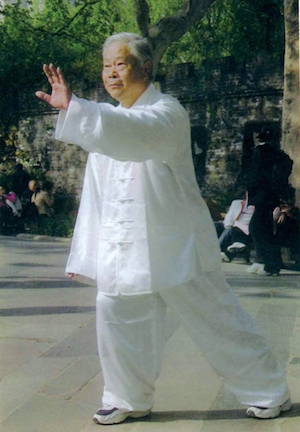

Lui Ji Fa – Wu Style Tui Shou Master

I first met Liu Ji Fa on a recent trip to Shanghai to visit my now retired and aging Taiji and Qi Gong Master Li Li Qun. Like Li, Liu was also a disciple of Master Ma Yueh Liang and also like Li he had held a senior position in the Jian Quan Taiji Boxing Association in Shanghai. Liu is still deeply involved in the larger family of Wu Style practitioners in Shanghai and is recognised as a specialist Master of Pushing Hands (Tui Shou) a practice that beyond any other area of Taiji now, has come to define Taiji as a martial art.

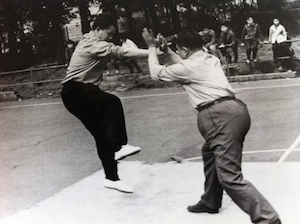

Master Liu and I met on a cold December morning in the park in Shanghai where I had studied over the years with Master Li. He arrived with some of Li’s old students and a few of his own. Liu is a warm and friendly man and after a formal introduction we fell into conversation. Liu explained his close relationship with Li and Master Ma and told me that he already knew of my background and dedication in the study of Wu styleTaiji quan and Qi Gong. He asked to see some form and I showed both slow and fast form. He was delighted and gave me the thumbs up. We proceeded to push hands and over the next 20 minutes he tested my skill and treated me to a remarkable display of his Tui Shou (Pushing Hands) skills.

His Tui Shou was incredibly soft and responsive and his adhering, sticking and following skills were of the highest level; combined with his exceptional Chin Na techniques he was a formidable challenge. His range of technique, accuracy and agility were fascinating and also alarming since I was on the receiving end. He kindly left me with some dignity (we had a sizable audience by then) though I was thoroughly disadvantaged. Nevertheless he seemed to be happy with my Tui Shou. It is always both a wonderful learning opportunity and a most humbling experience to Push Hands with someone who has achieved such a high and subtle level. There is a certain quality that I observed over the years in true masters, notably Grandmaster Master Ma Yueh Liang , my Master Li Liqun and now Master Liu Ji Fa, of ease and comfort and a deep sense of stillness within the attack and defence exchanges that comprise advanced Tui Shou. Their ability to listen and interpret, manipulate the joints, the spine and the ‘centre’ is extremely skilled and very soft, minimal and for the most part invisible until it is too late. Typically they seem to do little to achieve much.

We ended our first meeting in the park with much laughter and happiness which I have come to learn is his most endearing characteristic and one which Liu attributes to the benefits he has accrued from the long practice of Taiji and the people it has brought him close to. He added that happiness and laughter were crucial ingredients in nourishing our life energy (Yang Sheng Dao) and staying young. Master Liu invited me to treat him as a brother, an Elder Teaching Brother, since I was already Master Li’s disciple and like Master Liu I am a 5 generation lineage holder of the Shanghai Wu Style of Taiji quan. Master Liu explained that although his first Teacher, a Master Pei Zhu Yin was originally a student of Wu Jian Quan he had been asked to become a disciple of Master Ma putting him back one generation below Ma thus Liu who was initially Pei’s disciple had become 5th and not 4th generation.

(My master, Li Li Qun is second from the left and Pei Zhu Yin is 4th in on the second row looking over a shoulder. I am told that this was a definitive record of all the senior disciples of Ma and Wu in the mid to late 1970’s )

Master Liu told me that he had been very close to Li, often training together. Li had also known Pei well. Because of their close relationship Liu said that he was more than happy to help me in my future Taiji development since Master Li could no longer do so. Obviously it was an invitation I could not refuse. It was sealed with a dinner surrounded by a few of Master Li and Master Liu’s disciples and a visit to the graves of Grandmaster Wu Jian Quan, Wu Ying Hua and Ma Yueh Liang to pay our respects to the lineage Masters. It was definitely my lucky day.

I returned to China in August this year to visit Master Liu with two of my senior students and he greeted us warmly and was incredibly generous with his teaching. We spoke at length one morning after our practice. I wanted to discover more about his first Master, Pei Zhu Yin and his own experiences in learning Taiji quan.

He told me that he first met Master Pei (1917-1986) in a park in 1964 near his home. They discovered that they lived quite close to each other. Pei was by then a disciple of Ma Yueh Liang. At that time, Liu had done a variety of different sports including western boxing and two years of Yang Taiji quan. Master Pei invited Liu to become a student of Wu Style and Liu began meeting Pei in the park daily to study the fundamentals. Liu said he spent 3 months just practicing the first movements of the form. This was the traditional method and tested both patience and integrity. Liu regarded Pei as a most interesting and somewhat unique figure in the history of Wu Style Taiji since he had studied for four years under Wu Jian Quan and was the youngest member to join the first group of student intake when Wu opened his boxing association in Shanghai in the mid 1930’s. Pei was one of about 20 students all of whom came from a wealthy strata of Shanghai society. Pei also went on to study under Wu Kong Yi, Wu Jian Quans eldest son whom he called ‘brother’ denoting their close relationship, before he became a disciple of Master Ma Yueh Liang. Liu told me that Pei had absorbed the teachings of three major Masters of WuTaiji quan which had given him a very high level of skill and a deep understanding and a unique place in the history of Wu Taiji in Shanghai.

Liu told me that Wu Jian Quan had taught three hand forms.. The first was the ‘Square Form” which he had taught his sons. Pei had also studied this form and it was the square form he taught to Liu. The second was the ‘Round Form’ which Pei had learned from Ma in the early eighties and the last was the Fast Form which Liu said was passed from Yang Lu Chan to Quan You and then to Wu Jian Quan and then to his two sons and daughter, Wu Kong Yi, Wu Kong Zhou and Wu Ying Hua and his senior disciple Ma Yueh Liang. It was the original hand form and was taught to family and close disciples. Master Ma became best known for this form and it was he who mostly demonstrated and taught the Kuai Quan. (Fast Form). It remained a secret form in China until around 1986 when it was first publicly demonstrated. Liu told me that Wu Kong Yi had taught a few disciples the Kuai Quan after he moved to Hong Kong but had concentrated more on the teaching of the ‘Square’ form’. The ‘square’ form is now referred to as the Wu Family form outside of China and is taught throughout the International network of Wu Family Academies under the leadership of Eddie Wu. In China the ‘round’ slow form is favoured as the essential expression of the Wu Style Taiji boxing and this was best represented by Wu Ying Hua who was and still is considered the standard against which the Wu style is measured. The Fast Form or ‘Kuai’ quan was lost to the overseas Wu Family line and I understand that it is not recognised or acknowledged in the current modern Square Frame tradition of Wu Family Taiji quan. Liu told me that the Square Form was designed to promote Gan Jin or harder energy and the round form was designed to promote the Rou Jin or softer rounded energy. Liu demonstrated the Square frame as he had learned it from Master Pei, giving it an extraordinary refinement and internal quality I had never seen before even though I am familiar with the form. This form is now rare in China and Liu may be one of the last Masters to truly understand its usage and characteristics. Liu thought that Wu Kong Yi may have standardised the movements more in Hong Gong as a means of teaching larger numbers of students which may have changed its ‘flavour’ and some of its original characteristics and techniques.

When I asked Liu about Pei’s methods of teaching he told me that Pei was an easy going teacher who taught in an unrushed way ensuring each movement was fully understood and well practised before moving on to the next. Pei gave thorough explanations for each movement and showed application and variations. After three years Liu had achieved a good level and Pei both liked him and recognised his talent. He made him an instructor and Liu began teaching Taiji quan. Pei died in 1986 and Liu became a disciple of Master Ma. Liu expressed his deep gratitude and respect for Pei Zhu Yin, his first master.

It was evident that Liu had benefited from a close relationship with Pei and had benefitted from Pei’s knowledge which had evolved from the three remarkable sources of Wu Jian Quan, Wu Kong Yi and Ma Yueh Liang. Beyond Master Ma and Wu Ying Hua, this gave Pei, amongst Master Ma’s disciples, a unique (as far as I know) experience spanning the modern evolution of Wu Style Taiji quan.

In my time talking and practicing with Liu, he referred to several key and defining principles that must be understood in the art of Tui Shou. He explained first that moral character and integrity are very important in the study and practice of Taiji and especially Tui Shou. Through the practice of Tui Shou it is possible to see clearly the personality and different character of the players. Tui Shou, can therefore be a tool for each person to study themselves. The civil aspect of martial arts, Master Liu said, is very important in China. In Taiji he said it is hard to achieve a high level without the correct mind set and moral integrity. By this he meant you must have a good intention to achieve the ‘Dao of Taiji’ and to be able to express this in your daily engagement within society, your family as well as co-operating to benefit your Tai Ji brothers and sisters. This attitude is valuable in both learning and teaching and is often (I have found) conspicuously absent in the West.

Master Liu explained that in Tui Shou each moment is not a competition to win or lose but an opportunity to understand something deeper and more profound. This aspect of training gives Taiji almost a unique position in the martial arts since it requires you to cultivate a ‘particular mind set’ which is seen as a critical aspect to the achievement of the art. It is most easily expressed in the training of ‘stillness’, the most crucial of ingredients in Taiji training whether as a therapeutic practice or as a martial art.

Liu said ‘stillness’ must be cultivated to allow real development. He was keen to emphasize that movement is born out of stillness and so stillness is the crucial ingredient in both form practice and Tui Shou. Stillness allows you to listen to and interpret correctly (Ting Jin, Dong Jin) your opponent. Stillness allows you to overcome the obstacle of resistance, which is both a physical and a mental state and to keep connected (Adhere, stick, join and follow) to you opponent. This includes the principle of ‘no resistance and not separating’ (Bu Diu, Bu Ding) which is a defining principle in Taiji quan boxing. It is incredibly hard to achieve since we are both conditioned and hard wired to use force and resistance when we meet force and aggressive intention. It requires a particular type of mindset and character and a massive investment in time and introspective practice to achieve since the skills required are counter intuitive. Master Liu said the mark of achievement is the level of stillness from which arises not only the martial skill but good character.

Master Liu demonstrated how from ‘stillness’, the most Yin of the Taiji principles, the Yang aspect can be trained. First soft and then hard. From the deep Yin comes the Yang principle. At a certain level, its martial manifestation can naturally and quickly convert to a variety of techniques, throwing, repulsing and trapping, but it must always return to stillness. Only by cultivating the first state can the second state truly emerge – that is the ability to change in a relevant way from one state to another (Yin to Yang to Yin) whilst maintaining an internal connectivity. It is this ability that Tui Shou trains. It takes a lot of ‘intelligent’ practice to firstly overcome your own resistance and mind set, second to learn to listen to the opponents force, direction and intention and third to learn to interpret and react appropriately whilst remaining still internally.

Most martial arts training strategies teach particular moves to suit particular attacks and then train those scenarios in a repetitive way. Wu Style Taiji specialises in interpreting each attack according to its own merits and characteristics. It requires you to learn a vocabulary of defensive principles first whilst maintaining a predominantly soft and neutralising, adhere and follow mode. Only then does it encourage an offensive response through exploring the conditions of attack. Within this context many variations arise without necessarily sticking to a fixed pattern. The naturally or spontaneously occurring response becomes more abstract and less ‘routinely’ oriented and indeed this is a characteristic of high level Tai Ji Tui Shou. The classic metaphor here is the soft flowing, all pervasive yet penetrating power of water. It is an easy and attractive idea to adopt but it is difficult to achieve and one that is outside the convention of many martial arts. However it is deeply rooted in principles and understanding those principles is at the very core of Tui Shou practice.

Master Liu further expounded the following key principles:

‘Walk like a Cat and Use energy like drawing silk’; cultivate Tan Tian as the key to all movement; ‘be still until your partner moves then arrive first’ and finally, ‘dissipate and redirect your partners force’. Without these principles Liu explained it was impossible to achieve Taiji Tui Shou. Liu insisted that practice must at first be slow to allow time to build a clear understanding of these essential principles as strategies..

The Shanghai Wu Style Tui Shou is characterised by 5 or so single hand manipulations and 13 core double hand manipulations and 5 Core stepping methods. It is this vocabulary of dynamic movement or ‘physical literacy’ that is used to develop the foundation defensive skills. Master Liu was able to show how the 13 hand manipulation evolved naturally into a myriad of constantly changing throwing, repelling and locking techniques. His footwork was also very creative and agile and he showed how the legs, beyond the normally taught sweep methods, could not only allow you to step strategically but could also be used for striking and trapping modes of attack to devastating effect. It is a seldom taught area of Taiji martial training.

Master Liu excelled in all areas of Tui Shou but in addition he showed some unique characteristics. The first was his ability to change shape and accommodate the opponents position, force and shape. By this I do not mean just to step around or evade, he had a unique at least in my humble experience ability to deflate either side of his chest separately and collapse or expand them at will. He was able to deflate his upper body and expand his lower body simultaneously and vice versa. He used this in Tui Shou to change shape and absorb direct pressure on his body. (He also used the strategy of leaning backwards which is not always associated with standard Taiji practice though it does appear in the Square frame and the weapons forms but not in the Round form as exemplified by Wu Ying Hua). His ‘morphing’ skills allowed him to inflate and repulse his partners creating the effect of bouncing off him or falling into him and then being thrown out. This ability was also expressed through his arms and joints as well as his torso. This more mysterious and high level Tui Shou skill is hardly seen anymore but it is a highly regarded skill in China and, as I understand it, a unique skill of Taiji quan. Master Liu explained how the opening and closing qualities associated with exhalation and inhalation served to make this strange effect possible plus, I might add, a staggeringly soft body which few of us will ever achieve. Breath, Master Liu said, was extremely important in both playing the form and the Tui Shou. Indeed control of the breath and Dan Tian was crucial to achieving a good or even a high level in both. Master Liu pointed out that both inhalation and exhalation could be interchangeable in neutralising and issuing energy, a strangely counter intuitive skill that I do not recommend anybody try unless you are at a very high level and can be guided by a master).

Master Liu also had a remarkable mobility in his joints and shoulder and waist girdle which he could use to dissolve force independently. This was not simple folding energy which requires sequential collapsing of joints and absobing force, but a more sophisticated control over the spine and joints especially the wrist, elbow and shoulder as well as the whole upper shoulder girdle including the scapula. Wu Style does in fact specialise in opening the joints to achieve an array of neutralising, absorbing and redirecting skills and this accounts for the occasional critisicm (especially of Wu Ying Hua demonstrating the Slow Round Form) that she does not rotate her waist (Pelvic girdle) in accordance with the classics exhortation that power is generated in the legs and controlled by the waist and that neutralising or redirecting force is the result of the turning ability of the’waist’. Whilst this is true the small circle expression of the Wu style does not only mean small steps and shorter arm range, but a small circle neutralising ability within the joints. In addition, once the Dan Tian is understood as a centre for reconciling forces and directing energy down as well as up sometimes referred to as “Dan Tian Rotating” and a distinct skill I have seen only in high level masters, this can happen without significant pelvic rotation. Nevertheless, the pelvic girdle (Waist) must remain loose and active though at all times stable. Interestingly, in advanced Wu style Tui Shou, the basic double push hands manipulations of Pung Lu, Ji and An are done with the body mostly centred with the hips and shoulders remaining relatively square on to the partner. The circles and vectors used to redirect and dissipate opponents force are not therefore the typical big horizontal circles generally associated with the large frame waist and torso turning seen in many Taiji styles and most Pushing Hands.

Master Liu also excelled in Chin Na or the ability to seal or lock up joints. He explained that different locations on the opponents arm and body lend themselves to different forms of locking/ sealing. Through constant practice and investigation and self refinement it was possible to achieve not only listening and interpreting skills but an ability, to use a therapists term, ‘palpate’ a joint or an area to create a ‘disruption’ or ’lock-down’ thereby enabling you to manipulate the joint and thus the opponents centre. Softness and a knowledge of anatomy helped. Mater Liu was able to do this also with muscle groups and this allowed him to control your centre as well as pull you in or throw you away from his. Master Liu had studied Chinese Accupuncture and Tui Na (Massage) and he was clear that this had enhanced his Tui Shou and Chin Na skills.

Not all great Masters are good teachers and even those who are blessed with the ability to transmit their knowledge must rely upon the willingness of the student to listen, experience and learn. I have been lucky that my Master, Li Li Qun who was an excellent teacher and able to show and explain his skills. Master Liu is the same. His patience and demeanour invite you to participate and learn and his personality and knowledge invite you to marvel at the skills of Taiji quan. Always smiling and happy he laughs often, expressing himself in an open and generous way. He is a link to an older and profound root of Taiji as a martial art and I am honoured to call him my brother. I will return to China soon to spend more time with Master Liu. Just as I thought my horizon was darkening with the retirement of my Master, another sun rises in the east to entice me further on the journey that is Taiji. Thank you Da Shi Xiong Liu Ji Fa.

Author: Michael Acton

is based is the Senior Instructor and Founder of Wu Shi Taijiquan and Qi Ging Association UK. and the Honorary Chairman is his teacher Dr Li Li Qun.

Images: Michael Acton