What do you think of when you think of your grandfather? I grew up hearing about one of my grandfathers through bedtime stories. He had passed away before I was born, and so my only experiences of him were through a handful of photographs and a set of colorful tales known in the family as “Grandpa Harry stories,” one of which involved a doctor riding a goat into the house. My experiences of my grand-teacher Professor Cheng Man Ching have been similarly from a distance, since I began my Tai Chi Chuan study shortly after he passed away. During my Tai Chi Chuan “childhood,” my classmates and I heard wonderful “Professor Cheng stories” from his students as they passed through town giving us workshops. “I was driving the Professor one day and he said to me …” or, “The Professor didn’t speak English, and I didn’t speak Chinese, but …” We heard these stories over and over again, and never ceased to be delighted by them. What was verbally handed down to us through his students/our teachers was supplemented by the color film, and by a thin English book with green covers by Professor, first published in Taiwan in 1962. That was the only book available at the time, and it had to be special-ordered through our teachers. When I myself later began to teach Tai Chi Chuan, I drew from this book constantly and would carefully study the book while riding the bus to class. When Professor’s other books began to appear in English, I read them avidly, and enjoyed the blend of Tai Chi, philosophy, and stories they contained. It was in these ways that I and my fellow students came to know and admire our grand-teacher, even though we’d never met him. When I entered graduate school, one of my main goals was to do research on Tai Chi Chuan. For one project, I decided to do a biographical sketch of Professor Cheng. I gathered materials during visits to Taiwan and New York City, and interviewed numbers of his students. I came to know more about him and to respect him even more. Because of school, I also became more familiar with the Chinese classics and began to see how thoroughly Professor’s work was imbued with a Confucian ethic. I came away with the impression that Professor had made some unique contributions to the field of Tai Chi study.

Professor Cheng’s essays and commentaries on the Chinese classics give us rare insight

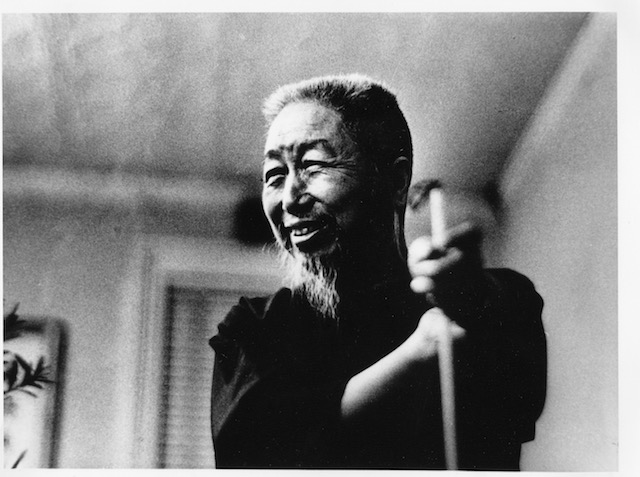

Professor Cheng continued for his whole life to carve out a literary and scholarly niche within the world of Tai Chi Chuan, that of a “Tai Chi philosopher.” His influential Cheng-tzu’s Thirteen Treatises remains without peer. His several form instruction books contain many gems, not the least of which are the photographs of him doing the Tai Chi form and tuishou. His essays and commentaries on the Chinese classics give us rare insight into the mind of a twentieth-century Renaissance man. His paintings and poetry give us beauty and grace. His movies show a man who mastered the integration of mind and body, substance and application. His broad mission may have been to “save” and promote traditional Chinese culture, but his humanity was also reflected in relationships with his many students. Professor Cheng, more than many other Tai Chi masters of his time, expanded the notion of what Tai Chi Chuan is about-that it truly was a “Tao,” a path for leading one’s life. This Tao went far beyond Tai Chi Chuan’s origins in martial arts and beyond its use as a health exercise. In Professor’s hands, Tai Chi Chuan became a means to “zuo ren,” to make oneself a good person. My grandfather taught his children, who in turn, taught me, my siblings, and my cousins. Even though I never met him, my grandfather’s influence has been passed down to me, whether in the color of my eyes, in a gesture, or in the ways in which I choose to live my life. In this same way, I would like to think that Professor’s work lives on in all of us, not just in the way we move or turn or step. I hope that we can measure up in some small way to his example of not only practicing Tai Chi Chuan and exploring its multi-faceted depths, but learning how to be a good person.

Professor Cheng Man Ching Series

Cheng Man Ching was also named the “Master of Five Excellences“. He was one of the first who taught Taijiquan in the West and his Taijiquan style is spread all over the world. Here you will find many articles about his teaching and how it is taught by his his students.

Cheng Man Ching’s way of teaching (4): On being a masterCheng Man Ching’s teaching was marked by underlining sameness and diversity at the expense of hierarchy and difference. This approach formed the basis of his unique way of bridging the cultural gap between East and West.

Cheng Man Ching’s way of teaching (3): On meditation Our idea of meditation is mainly influenced by two aspects, the visual and the practical aspect. The mind’s uniform picture of a meditating person is someone sitting still in a peaceful environment, in a monastery or on a mountain.

Cheng Man Ching’s way of teaching (2): The Dantian The discussion about the nature of the Dantian is old and it remains unresolved until today: Is the Dantian a bodily, material reality or an ideal concept of Traditional Chinese Medicine to explain certain psychosomatic correlations? The debate cannot simply be described as a conflict between East and West or between Tradition and Modernity.

Cheng Man Ching’s way of teaching (1): “I am not a guru.” Cheng Man Ching, student of Yang Chengfu, came to New York in the 60s, at first teaching Taijiquan in the Chinese community, later also teaching Westerners. Being a university professor from a family of scholars and deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture, he was confronted with flower children searching for a guru.

Cheng Man Ching on the dao of Taijiquan – a poem Cheng Man Ching is portrayed by his students as an example of total dedication and commitment to the Chinese Arts, especially concerning Taijiquan.

Self-massage as taught by Prof. Cheng Man Ching Cheng Man Ching was known as a master of the five excellences. As a teacher, he taught calligraphy and Traditional Chinese Medicine as well as Taijiquan, Push Hands and sword fencing. Advocating Taijiquan as a method of self-cultivation and health-preservation, he also used to teach his Taijiquan students aspects of other Chinese arts.

Author: Barbara Davis Editor, Taijiquan Journal, Author, The Taijiquan Classics: An Annotated Translation

Images: Ken van Sickle