Five Faces of Tai Chi: When people only know of or focus on one aspect of a system, they commonly mistakenly think they are able to discern all there is to it. Tai chi chuan and the related art of ba gua chang are many things under one roof. Traditionally both have five faces, some of which are more popular, well-known and more widely available than others. Each layer or face takes you closer toward the internal martial art’s deeper possibilities and full potential.

In my own journey studying internal martial arts and eventually becoming a lineage holder in ba gua, tai chi and hsing-I, culminated in 11 years in China where I came to understand the five faces of tai chi as follows:

Sophisticated physical movement forms to promote and maintain health and wellness.

Paths to developing the full range of Taoist energy techniques called the 16 nei gung.

Comprehensive fighting systems.

Chi gung systems for using chi to heal a wide range of specific diseases in patients.

Spiritual paths within Taoism.

Mastery of Tai Chi Is Similar to Mastering Any Subject

University students can’t reasonably expect all their teachers or teaching assistants to have a Ph.D. much less five different Ph.D.s in specific related areas within one field (say history, chemistry or tai chi). As in any field, unless you are an absolute specialist in tai chi, you may only focus on one small area or face of the art—unaware, uninterested or not accomplished in its other aspects. Therefore it is common that most people who practice tai chi are neither fully skilled nor equally specialized and trained in all of tai chi’s five faces. Likewise in terms of learning, teaching, and levels of achievement, people have varying degrees of natural talent and capacities: ranging from low to ordinary, to exceptionally high or even those we call “masters.”

In the mid-1960’s, after several years of doing Japanese martial arts, shiatsu and Zen meditation in New York, I got turned on to tai chi by Cheng Man Ching—so much so that over time I became determined to answer a complex question: “What is the full possibility of this marvelous art and cultural gem called tai chi?” This personal odyssey from 1968 to 1987 required that I become fluent in Chinese and spend more than a decade of my life, full-time, completely immersed in the study of the five faces of tai chi chuan, ba gua chang and related fields.

Since returning to the West in 1987, I have taught the five aspects of tai chi to over 15,000 students in the United States and Europe, certified over 300 instructors and written seven books in the hope of sharing and spreading the wonderful knowledge I was fortunate enough to encounter. Parts of my two books Tai Chi Health for Life and the newly revised and expanded edition of The Power of Internal Martial Arts and Chi further explore and fill in the blanks regarding this most interesting question. My other two chi gung books and two books on Taoist meditation explore the context and technical how-to sides of tai chi, chi gung and Taoist meditation.

Face 1: The Appearance of Outer Physical Movements

Without understanding the background and context of anything, the first impression you can get from watching tai chi ranges from accurate, to partially misleading or even downright deceiving. Beyond personal opinion about the look of the aesthetic physical form, the movements of tai chi were originally designed to perform specific functions. They provide valuable benefits, especially in terms of fostering general health, healing and stress relief—the primary reason why 95% or more people practice the art of tai chi today.

When most people first see someone do a slow motion tai chi form, regardless of style, what do they see? They tend to classify any martial form that even remotely looks like tai chi as being one and the same. “I mean, it’s all just tai chi, right?” I’m asked. Most Westerners think of it as some Oriental movement, slow-motion karate or dance fad where people move in slow motion. Yeah, right!

They see people moving in a choreographed way, sometimes with funny looking weapons primarily moving in slow motion and sometimes too quickly to discern. Maybe some of them have even seen two people touching without breaking contact, moving either fast or slow, doing something called “push hands.” Others might have witnessed martial artists sparring with each other to which the response is typically, “This is for health? Uh? How can this all be the same thing—this tai chi thing?”

What Is the Purpose of the Physical Movements?

To see the potential of tai chi’s physical movements requires peeling away the tai chi onion, step by step, from its surface down to its core. These include:

- Providing the body the necessary exercise it needs to stay healthy and mobile. Most importantly, tai chi is practiced in a way so gentle, it can be adapted by virtually anyone regardless of advancing age, low natural level of coordination or degree of chronic injuries yet it still maintains many, powerful benefits. This is not the case with most sports or martial arts.

- Creating and maintaining a high level of general, physical wellness through several basic mechanisms such as training the body so it neither dissipates nor blocks its fundamental chi flows, creating better movement of all the body’s fluids, continuous compressions and releases, and chi flow within and between all your internal organs.

- Creating and maintaining a high level of general stress release and mental well-being. This occurs through tai chi’s many specific training methods geared toward physically relaxing the body’s muscles and nerves which results in a powerfully effective form of stress management. Progressively the practitioner becomes capable of focusing strongly with a relaxed rather than a tense mind—something modern computer users need desperately.

- Physical education containing sound principles for teaching the bio-mechanics of beneficial, whole-body movement. Tai chi’s principles and techniques can be creatively adapted to achieving higher performance in a wide variety of sports and physical activities. At the very least, tai chi can increase the joy of doing any form of physical movement. This quality often prompts those who don’t know the inner workings of tai chi to give what they perceive to be a great compliment “Oh, tai chi is such a beautiful dance and you do it so gracefully.”

Healing the body of a wide variety of specific diseases. The movements of tai chi were designed to implement the principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Even tai chi done poorly—without regard to implementing the dictums of tai chi’s primary theoretical text Tai Chi Classics—will work reasonably well. Likewise the extent to which these principles and tai chi’s internal chi techniques are adhered and implemented, the physical healing potential of tai chi becomes more of a reality. - Enhancing the longevity potential of the human lifespan. In China, half of the people who do tai chi begin after age 50. The two classic stereotypes of Chinese tai chi practitioners in China are that they are compromised of the sick wishing to get well and seniors wishing to rejuvenate their body and diminish the degenerative effects of aging. In the West doctors are more commonly recommending tai chi to their patients for the same reasons, especially with an increasing number of scientific studies showing its clear and potent benefits for overall health and well-being. For example, tai chi is used as a low impact exercise method for reducing blood pressure, mitigating arthritis, and increasing balance and thereby preventing falls and broken hips by the elderly.

- A repertoire of martial arts movement techniques and principles. Although not obvious to the non-specialist, all the movements in tai chi forms, such as the kata of karate, contain the various potential ways punches, kicks, hand strikes, joint locks and throws as well as a wide variety of weapons techniques can be performed.

- An efficient container for the most valuable internal content of the second, third, forth and fifth faces of tai chi.

Tai Chi Styles

At another basic level the specific qualities of the physical movements identifies which particular tai chi style, or subgroup within it, is practiced. Most who are unfamiliar to tai chi don’t know there are different styles, much less the subdivisions that exist within the individual styles themselves. When looking at the level of physical movements alone, many experienced tai chi practitioners who have done only one style, might not “get” what’s happening in another style. This is either because they scoff that it’s “not my style” or they lack a broader tai chi education.

Some might notice one form is done standing higher, knees less bent, with tighter less obviously extended arm movements—mostly the Wu, Sun or Hao styles—the “smaller frame” styles. While others may notice that some forms are done with lower stances and more obviously extended arm movements—Yang and Chen styles—the “larger frame” styles. This said, approximately 85% of all tai chi practitioners do the Yang and Wu styles, which are basically variations of each other, while 15% do the original Chen, Hao and or one of the ten or so more common combination styles such as the Sun style. The serious practitioner will want to be well-versed in as many styles as possible. Without going into the history of it, the Wu and Yang styles are actually quite similar—with the Yang styles typically having bigger movements and the Wu style typically having smaller more condensed movements which perform the same function. I personally teach the Wu style—although I did teach the Yang style for many years in the 1970’s—because of its connection to meditation. When I teach, especially in my Instructor trainings, I find that serious students are looking for insights as to how the forms, which are essentially the same.

Face 2: Activating Chi and the Normally Invisible Anatomical Structures

Whereas the overt physical movements of tai chi are gross, its subtle component involves chi flow. How to develop, balance and increase your personal chi and the ways it translates in real time is not just philosophical, emotional and mental but within the practical functioning of the physical body. This necessitates you to simultaneously and consciously activating the invisible anatomical structures deep inside the body: internal organs, joints, fluids, etc. Affecting these visually invisible processes with tai chi happens through its chi work and a conscious melding of the mind’s intent with precise adjustments of the form’s outer movements.

Chi development is central to the higher levels of the art. This aspect of tai chi is usually less available due to a general lack of sufficiently trained and knowledgeable teachers. Individuals with sufficient generosity and skill need to be both willing and able to share their knowledge and make it comprehensible without all the mumbo jumbo. Generally the best scenario is to find an instructor who can effectively combine sound physical-body and chi principles when teaching how the movements are done. However, this is often not the case.

The ancient idea of chi—subtle invisible energy, your life force—is that it enables everything to move and function. This belief permeated the cultures of tai chi in ancient China. Chi methods and specific techniques within tai chi and related arts are composed of 16 large areas, called in Chinese the 16 nei gung components. In the late 1990’s I first introduced these ideas in the original edition of the Power of Internal Martial Arts.

The 16 Components of the Nei Gung System

The Taoist science of how energy flows in humans is derived from the following components of nei gung:

- Breathing methods from the simple to the complex.

- Moving chi along the various ascending, descending and lateral connecting channels within the body.

- Adjusting body alignments that prevent the flow of chi.

- Dissolving, releasing and resolving all chi blockages.

- Moving chi through all the acupuncture channels, energy gates and points.

- Bending and stretching soft tissues from the inside out and from the outside in, along the yin and yang acupuncture channels.

- Openings and closings (pulsing).

- Working with the energies of your aura or etheric body.

- Generating circles and spirals of energy inside your body.

- Absorbing and projecting chi and moving it to any part of your body at will.

- Awakening and controlling all the energies of your spine.

- Awakening and using your left and right energy channels.

- Awakening and using your central energy channel.

- Developing and using your lower tantien.

- Developing and using your middle and upper tantien.

- Integrating and connecting each of the previous 15 components into one unified process.

Nei-gung has two salient qualities:

- If sensitive enough you can both consciously feel chi and directly move and activate the chi inside your body in the ways described in the previous list, using each of the 16 nei gung components.

- Regardless of whether or not you can initially feel chi, over time working with the 16 nei gung components will enable you to consciously feel and activate the anatomy inside your body to move in specific, prescribed ways. Two examples are: 1) Most people cannot feel blood moving deep inside their internal organs although it is happening anyway. Likewise, whether you can feel it or not, using nei gung you can consciously boost the ability of all your body parts, including your brain and internal organs, to activate and perform optimally. 2) Although many cannot normally feel chi moving in their acupuncture meridians, when a good acupuncturist puts needles in you, it becomes possible to viscerally feel the chi moving through your meridians.

In the same way, while many can’t feel the cause, chi, they can feel and consciously control its physical effects in conjunction with tai chi’s physical movements. These include the ability to change internal pressures within the body, and feel physical fluids moving in the body in specific ways, such as within your blood vessels, joints, around your spine and brain, and between your internal organs. While doing tai chi you may experience subtle or easily felt waves moving through the body Even if initially you are insufficiently sensitive to directly feel chi, it is quite possible to consciously smooth the pounding in your heart or lower your pulse rate. Within the movements of tai chi are methods for feeling and controlling the ever more subtle forms of emotional, mental, psychic and karmic chi and even the chi of the very essence of ourselves, our souls.

Some say chi is only a belief, that it doesn’t exist as it can’t be seen and most especially “I” can’t personally feel it. In many ways this is a similar debate that raged in the 1950’s as to whether or not the quantum field existed. As the argument went, it was only a mathematical speculation without physical proof.

Breathing techniques are essential. However they are not all or even most of the ball game with regard to developing chi. After all, although breathing is the first component of nei gung, let’s not forget the remaining fifteen! Even more important is the invisible way through which the mind’s intent tells the body what to do and thereby creates a physical structure of precise outer movements. This is a structure that the mind can piggyback onto, and thereby go inside the body so it can motivate and activate the invisible anatomical structures deep within, for example to open and close tissues and anatomical parts deep inside your joints, abdomen, spine and brain. Then you can direct your chi to wherever you want it to go, to create hundreds of both general and highly specific effects.

The way I have taught the 16 nei gung for the last 20 years is through a chi gung program consisting of six core courses. I’ve found this is the easiest, most accessible and valuable method for teaching beginning and intermediate students all the parts of the nei gung.

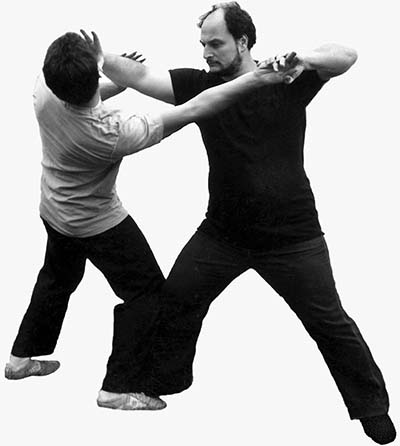

Face 3: Martial Arts and Self-Defense

The general public and many hard core external martial artists do not tend to associate fighting skill with tai chi. Most practitioners clearly do not use it as a combat martial form and perform only the physical movements and rarely if ever even do the lightest of pushing hands. If any martial art is to be “martial” people must do some sort of active sparring, with punches, kicks, throws, joint locks and preferably also some weapons training. Tai chi and ba gua have several distinct levels of self-defense or martial arts applications. At each level of depth, there are progressively fewer practitioners. The progression is as follows:

- Simplistic understanding of how the form movements can be used for self-defense and thereby bringing the form alive and making the moves easier to remember.

- Tai chi martial arts “lite” for those who primarily practice pushing hands or its variations only as a recreational activity.

- Slightly more severe martial arts medium with competitive pushing hands and various kinds of lighter recreational sparring, the play aspect of self-defense training, with or without gloves, joint locks and throws.

- Martial arts heavy, ranging from those interested in more realistic and free form unrehearsed fighting applications, the ability to take blows unharmed and training for full contact competitions.

- Martial arts severe all the way into the heaviest realms of tai chi for practical use in life and death situations, such for bodyguards, police work and the military.

The martial arts face of tai chi is mostly practiced by young men. When discussed tai chi as a martial art tends to suck all the oxygen out of any room, mostly due to the extreme passion and commitment of those into it, especially in tai chi or martial art magazines and books. However it is useful to consider that for tai chi to translate into actual self-defense requires the practitioner to put in a lot of time and effort to recognize and deconstruct the techniques themselves. Endless hours of solo and sparring training are required to translate the possibility of any martial art technique into the actuality of real-life applications, whether using it in a playful way or under progressively heavier situations. To achieve this, knowledge of only the techniques themselves is insufficient; hard work and progressive, time-consuming, solid training programs are required.

My most in-depth training was in the Yang and Wu styles and I teach the martial arts applications with an emphasis on the fighting techniques rather than only push hands, which I view as only a training exercise. My teachings emphasized the fighting aspect of external and internal martial arts for forty years, but during the past five years I have been shifting my teachings from primarily focusing on fighting to meditation since I see that it’s more valuable for most Westerners.

Face 4: Applications for Medical Needs

Today’s practitioners of tai chi and ba gua are usually more well-known as being energetic healers rather than masters of physical combat. On one level tai chi and other chi arts are simply sophisticated forms of chi gung. The branch of Chinese medicine based on healing the human body and its chi without any external substance (such as herbs, needles, salves or bone setting materials), is called chi gung tui na. It has two basic divisions:

- Hands-on energetic healing techniques for projecting, absorbing and transforming the qualities of a patient’s imbalanced chi.

- Teaching people specific ways to modify the chi movements of tai chi, ba gua and various chi gung systems to heal specific illnesses. This is not just in a general sense as the first face of tai chi can do, but for severe and specific illness normally requiring medical attention. For example, Cheng Man Ching used the Yang style of tai chi to heal his tuberculosis and I used the Wu style to heal my broken back after an accident 25 years ago. An herbalist gives prescriptions and periodically adjusts the herbs in the formula as the healing process goes through its natural stages of development. Similarly, by practicing ba gua or tai chi with proper guidance and specific information regarding how postures are to be done to rehabilitate the chi of their own body, patients can regulate their own chi and become healthy. This is another most valuable face of what the tai chi form can do.

Generally, this aspect of tai chi is less available due to a general lack of qualified personnel who are willing, sufficiently trained and able to share it with sufficient skill as is the case with nei gung and traditional Taoist practices. There are three basic types of medical applications within tai chi using its form and related chi gung techniques to:

- Heal those with a wide variety of specific and often severe medical illnesses or disability.

- Regenerate the bodies of those physically traumatized or crippled, including the elderly.

- Reverse severe forms of stress, psychological problems and post-traumatic shock.

I consider my studies in chi gung tui na to be some of the most valuable training I received in China while studying with Grandmaster Liu Hung Chieh. This is a subject matter that I plan on teaching more of in the future. People learning chi gung tui na need to be reasonably good at chi gung itself before they can start applying energetic techniques to other people. Unlike 20 years ago, there are now enough people in the chi field with the experience needed to open up this subject and hopefully make a difference in the illnesses and diseases likely to present themselves in an aging baby boomer generation.

Face 5: Spirituality and TAO Meditation

There is the body and the soul. The first four faces of tai chi can effectively benefit the body-mind connection. A wide range of energetic imbalances of the body and mind can cause immense physical stress and make you ill. However, humans are more than their physical bodies. It is their being or human soul that the fifth face of tai chi is about. Given the growing spiritual poverty accompanying material abundance in the Western world, this spiritual face may ultimately be the greatest gift tai chi has to offer the modern world.

The fifth and least known side of tai chi enables the practitioner to actualize the spiritual meditation techniques of Taoism as a living tradition rather than an abstract idea buried in an ancient book that is no longer applicable to modern life. Taoism is the source of tai chi and ancient China’s original religion and spiritual tradition. Today it continues to provide valuable practical benefits for human beings regardless of which culture they were born into. This final face of tai chi involves non-ordinary mental and psychic applications and related practice methods within the context of esoteric spirituality. Its function is the journey into enlightenment within the living spiritual tradition of Taoism.

The core of vibrant and living spirituality intrinsically must be felt and directly experienced. Dead words and moral pronouncements alone are not enough. Living spiritual traditions of Asia are found in the pragmatic techniques and training methods of its meditation schools. Meditation methods enable the wise words of spiritual texts to come alive and be implemented in the real, day-to-day, living experiences of people. Although books may give the hint of what spiritual food might taste like, meditation practices have the potential to put the food in your mouth, give it flavor and ultimately make it digestible in daily life.

As a lineage holder in the Water tradition of Taoist meditation passed down from Lao Tse, I have developed an accessible, pragmatic program to teach these techniques, which I call TAO Meditation.

Meditative or Meditation?

Most practitioners of tai chi or ba gua to greater or lesser extents do it as a meditative exercise rather than from an Eastern or Taoist perspective as meditation. So, how are they different?

Doing tai chi in a meditative way calms you down, relaxes your muscles, releases your nerves and reduces your stress. However, from the perspective of meditation it is only the first step in a much longer journey. This first step can be accomplished by activating the first two faces of tai chi and ba gua—namely good, smooth, regular physical movements (first face). Ideally the practitioner would also simultaneously engage his/her inner chi practices (second face), which can result in healing stress-related physical and mental illnesses (fourth face). These will give the mind a sense of calm expansion and release from the physically felt pressure of the sense of time. Essentially, these meditative benefits can be achieved primarily through releasing the knots and blockages of the physical body and the physical chi which regulates it.

As a spiritual practice Eastern meditation and TAO meditation specifically go beyond this. You go beyond making the body and mind feel and function well to traveling the path toward enlightenment, becoming totally free, natural and compassionate at the deepest levels of your being or soul. To do this you must relax all your energy bodies and balance your chi. It is mandatory that you release all your internal blockages starting with the physical body and progressively moving through the emotional, mental, psychic and karmic bodies and essence of your being before going on to the final stage of enlightenment. The standards for tai chi as a meditative practice are quite different and significantly less precise to those for it as a meditation practice.

Five Practices of Meditation

Chi gung and TAO meditation are composed of five basic kinds of practices which complement each other and within which all their techniques are included. These are standing, moving, sitting, lying down and interactions between two or more people including push hands, sparring and sexual practices. Each of the five applications uses the 16 nei gung (second face) components and adapts them to its own unique way of practice.

Each of the five practices begins essentially as a chi gung practice for the needs of the physical body. Then after having a foundation in chi work or nei gung the next phase progresses to meditation. By releasing the blockages within the depths of oneself, it becomes possible to most fully develop the emotional, mental, psychic, karmic and essence aspects of a human being and thereby make spirituality something very tangible in meditation. This is the deepest inner work of all chi practices including ba gua, tai chi and chi gung. Tai chi as meditation is done within two specific contexts:

- Solo, only by yourself. It is essentially a complement to and equal partner in the Taoist sitting meditation traditions, which also includes within it standing, lying down and moving form practices such as ba gua, tai chi and chi gung. There is no connection to the physical combat side of tai chi in this case.

- As part of the Taoist spiritual martial arts tradition, including solo meditation practices and all manner of physical sparring training with or without weapons.

At one of my Instructor’s schools in Ulm, Germany, I teach aspects of the nei gung within TAO meditation every year because this is specifically what the students there want and I something I will teach again in April 2008. After teaching martial arts for over 40 years, I think the power of meditation in today’s thoroughly stressed, hurry up, over-caffeinated society is invaluable training that I hope to share with more people in the years to come.

What Is a Spiritual Martial Art?

The quest for spirituality is optional in martial arts. Spiritual practice develops the potential for a martial artist to become a great spiritual warrior in the battlefield of life.

Simply put, if “martial art” inherently means the art of the fight and “spirituality” the art of becoming enlightened, spiritual martial arts is the art of seamlessly integrating both. Its distinguishing characteristic is an unwavering commitment and emphasis on meditation and spirituality. In this context, martial artists go beyond only acquiring and practicing techniques for physical self-defense and combat. They now learn how their minds and spirits impact their inner worlds as they fight. Metaphorically speaking, training in the internal martial arts becomes the outer form or glass, which holds the water of spiritual exploration and awakening.

Tools of fighting are found in the body and in the mental strategies that accompany them. The tools of spirituality are found in the martial artist’s heart, mind and spirit, and the energies that allow them to function and connect to each other, as well as the ways they direct a person’s awareness and intention.

Instead of only battling and defeating external opponents, in the quest for spirituality, martial artists tackle the internal, spiritual foes that live in the depths of their souls. In doing so, they take on the greatest challenge of human existence: to become relaxed, balanced, natural, compassionate and free at the deepest core of themselves. If successful, they will emerge forever connected to—and not separated or alienated from—all of life’s experiences.

Spiritual martial arts can provide martial artists with the skills to genuinely encounter and embody spirituality, until they wake up and live from a continuous awareness of the consciousness which connects them to the chi that pervades the universe, working towards what in the East is called the TAO of enlightenment.

Working with Balance and the Qualities of Yin and Yang

Yin-yang relationships are infinite. Both ordinary and spiritual internal martial arts study them in depth. The recognition and efficient use of the seemingly opposite yin and yang qualities within spiritual martial arts increases physical and mental capacities. Learning how yin and yang work begins within your physical body and eventually extends to all eight energy bodies. Each energetic body has distinct areas where various aspects of yin and yang show themselves and manifest differently.

From a simple physical perspective, this could entail how either the arms or legs straighten or go forward away from the body (yang), or retract and come closer to the body (yin). From a simple physical chi perspective one might look at how chi movements can work offensively (yang) or defensively (yin). One might alternately project (yang) or absorb (yin) chi from the same or different body parts. Alternatively, in different ratios and in opposite directions one might simultaneously absorb or project energy with the same or different parts of the body, for example out of the extending hand and backwards from the spine.

Understanding the details behind each of the many yin and yang relationships enables the flow between them to operate optimally without internal resistance and become balanced, so one does not adversely affect the other. The potential of yin and yang becomes fully actualized, as martial artists gain the ability to fluidly change from one state or attitude to another, rather than remaining shrunken or frozen in their emotions, thoughts, psychic intuitions, karmic flows and individual essence or soul.

For example, emotional yin–yang qualities (the yang quality in the paired words is first) include anger–fear, hope–despair, enthusiasm–paralysis and joy–depression. Mental and thought driven yin–yang qualities include stability–flux, time–space, making it happen–allowing something to unfold and taking instant action without reflection–understanding what is going on.

The Heart-Mind and Releasing Yin or Yang Fixations

At either end of any yin-yang energetic quality, martial artists can easily become fixated or polarized. Rather than a smooth flow between a yang and yin quality, it becomes a polarized yang vs. yin quality (one being “good” or right, one being “bad” or wrong). If sufficiently conditioned by the past influences in their lives, practitioners can lose the capacity to fluidly change when necessary. They may know they are addicted to staying in the same emotional, mental, psychic or karmic rut, yet continue to “sin.” Even if they genuinely want to stop, try as they might they can’t.

The cure to this spiritual disease of fixations lies not only in better skill with fluidly working with the qualities of yin and yang matched pairs. It also means accessing the source that gives birth to these fixations in the first place—the Heart-Mind or the awareness of awareness itself. When this occurs, martial artists are able to release the specific yin or yang energetic polarization, reabsorb their energies into the core of their energy matrix and reappear without fixation or energetic charge. Besides the Heart-Mind, the Chinese and Taoists also call the quality that allow any yin-yang to come into existence “tai chi”—as in the Taoist phrase: “Tai chi gives birth to liang i.”

In terms of yin-yang, the energy of tai chi is neutral. It is all-encompassing rather than polarized. For a human to use it requires accessing the Heart-Mind (awareness of awareness itself) and releasing the energy of the specific yin or yang quality into emptiness, so in the future it can become anything, without the obligation or tendency to assume any specific form.

As it is neither and both yin-yang, it is the spot martial artists arrive at when they successfully release a blockage using the Inner Dissolving method. When the Heart-Mind is applied to focus on resolving specific yin-yang fixations, it ultimately enables the Inner Dissolving method to get the job done at a significantly faster pace than is otherwise possible with virtually any other technique. The Heart-Mind can remove the deepest psychic and karmic scars from the martial artist’s soul.

Spiritual Martial Arts are not for the Faint-Hearted

Spiritual martial arts provide a rapid, but intimidating spiritual path. Why? Sparring is intense. Spiritual martial arts use the scary, in-your-face, quality of combat to enable martial artists to access and quickly recognize the many kinds of spiritual nonsense potentially at the core of their soul.

As they deliberately place themselves in the path of danger and crisis, they are guided by their teachers to deliberately and consciously recognize the unconscious spiritual muck and grime that encrusts and binds their souls. This helps short-circuit the tendency for martial artists not to deal with their inner demons, which they could easily avoid or deny under lesser pressure or in non-combat situations.

Spiritual martial artists are then taught to metaphorically clean house with Taoist meditation techniques in all modes of practice (standing, sitting, moving, lying down or in relationship to others). This occurs at a significantly more accelerated rate than the relatively passive approach of most meditation methods. This situation can be compared to how a piece of coal (spiritual darkness) can turn into a diamond (spiritual awakening).

Spiritual martial arts using sparring and combat techniques do the same task in one or few lifetimes by metaphorically squeezing the coal with super-intense pressure. What makes spiritual martial arts a genuinely accelerated spiritual path is that it enables martial artists to confront their scariest inner demons rapidly, not slowly. This is not the 10,000 lifetimes cleansing process.

Author: Bruce Frantzis

Bruce Frantzis is the author of seven books including The Power of Internal Martial Arts and Chi, commonly referred to as the martial arts bible; Tai Chi: Health for Life; two TAO meditation books and Opening the Energy Gates of Your Body. He has studied healing, martial arts and meditation since 1961 including 16 year training full-time with renowned chi masters in China, Japan and India. Since 1987, Bruce has taught over 15,000 students and certified over 300 instructors worldwide.

Images: Bruce Frantzis