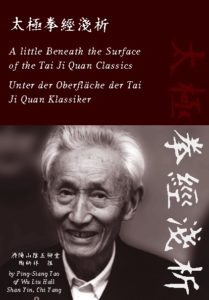

A little beneath the surface of the Taiji Quan Classics

Here you can find a translation of the Taijiquan Classics. Dr. Tao Ping Siang translated the Taijiquan Classics into English for his Western students. The first book, including the Chinese original texts, was published in Taiwan 1966. I had the great honour to publish that book for my second teacher in German. The book „Unter der Oberfläche der Klassiker des Tai Ji Quan“ was published in 2000 and is now out of print/sold out.

Dr. Tao died in Columbus, Ohio in December 2006. The heir of Dr. Tao, Dr. Shan-Tung Hsu generously gave the permission to publish the German and English texts on Taiji Forum. Shan-Tung Hsu said: “I am pleased to consent to the publication. In this way Taijiquan enthusiasts are enabled to profit from Dr. Tao’s work.“ (nk)

A little beneath the surface of the Taiji Quan Classics

Recommended reading on Taijiquan Classics

A Model of Persistence in an Art: Mr. Tao’s “A Simple Analysis of the Classics and Theories of Taijiquan”

By Chou Teh-Pei

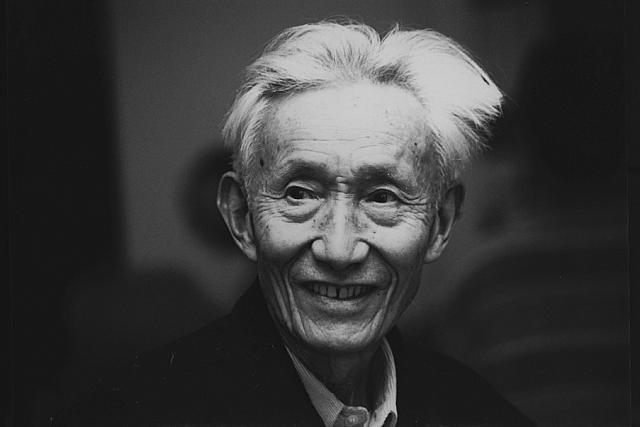

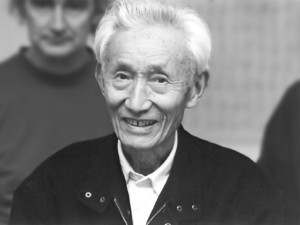

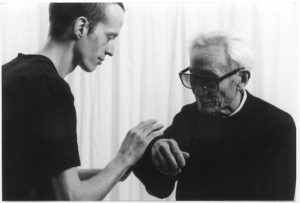

Mr. Tao was originally an expert in aviation mechanical technology, but he has devoted himself entirely to the study and development of Taijiquan, also known as Shadow Boxing, a unique Chinese martial art based on the principle of overcoming hardness with softness. I am proud to have the unusual opportunity to write a preface for Mr. Tao’s book, which tells what he has, learnt about this art and contributes to those who are interested in learning it.

Mr. Tao and I come from the same province, and we both served in the Chinese Air Force when we were young. I was able to learn Taijiquan from Master Cheng Man-Ching because I was guided in the elementary course by Mr. Tao. Even though my own knowledge of Taijiquan is very poor, and I do not want to pretend to know enough to comment on his book, I cannot refuse to write this introduction. So, rather than talk about Taijiquan, I will talk about how Mr. Tao developed his skills, since I have come to know something about this as a result of our long friendship.

Mr. Tao has studied several Chinese martial arts. From childhood, he has studied Spring Leg, which belongs to the Shaolin style. After studying with many teachers of many schools, he gradually turned toward the Nei Chia (inner) systems. He learned Hsing-I, Pa-Kua Chang, and also Liu-ho Pa-fa (also known as Water Style) and Taijiquan; those who taught him were all famous masters.

Although he might not have attained a high level right at the beginning of his studies he was influenced by all that he heard and saw, which was very helpful when he later came to integrate the knowledge he had gained through understanding the relationships among the different disciplines. Since he is not a show-off or shameless self – promoter, Mr. Tao is not known to the general public. His present level of achievement is the result of accumulating experience through long study and practice, and his joy in exchanging what he has learned with others who share the same principles and approach the subject with the same aims. Even now, he continues to seek advice and absorb new knowledge.

Mr. Tao also has single-minded dedication. He has left others far behind in his devotion to studying this art. His study of Taijiquan from Master Cheng Man-Ching, after arriving in Taiwan in 1949, actually dated from the time just before he returned to his family home soon after the end of the war with Japan in 1945. At that time, his Taiji teacher gave him an introduction to Master Cheng, but because he lived in Shanghai and Master Cheng did not, he failed to make contact with him and thus his chance to study with Master Cheng was delayed for four years. When he heard that Master Cheng had also come to Taiwan, he made a special trip to visit the master in Taipei. After he was received by Master Cheng as a disciple, he gave up everything he had learned before, and stared learning again from the beginning. As a soldier, he had to live in camp, and it was impossible for him to visit his Master everyday. Instead, he would consolidate all his leave and rush to Taipei from Tainan (from the south to the north of Taiwan) every month or so. This lasted four or five years. Later, when he had been transferred to a post near Taipei, he lived in Master Cheng’s house for a long time.

In addition to having this single-minded drive to learn, Mr. Tao also loves to ponder deeply; whenever he was given a piece of teaching by his master he would think about it day and night in an effort to gain a complete understanding of it. This is really the attitude described in the Doctrine of the Mean (Chapter XX, section 20) as not giving up as long as there is anything on which one has not reflected, or on which, having reflected, one has not comprehended.

Taijiquan is a form of boxing, which must be based on the cultivation of one’s character so that one can overcome hardness with softness. To give up what one has learned in order to follow another’s teaching requires a modesty also based in the cultivation of one’s character. Master Cheng’s book on Taijiquan advised students to avoid willfulness, insistence, and stubbornness, and to abandon self-assertion; in general, it is a method described as “investing in loss”. These are just the tasks that are required in cultivating one’s character. Mr. Tao’s cultivation of his character has a close relationship to his achievements in Taijiquan. He is modest, patient, and unwilling to show off. He is indifferent to wealth and fame, and so he is always happy and relaxed, physically and mentally. Thus it is naturally easier for him to realize fully the art of subjugating hardness with softness. This kind of cultivation is easy to speak about, but it can only be attained through constant, determined practice.

I am very happy that Mr. Tao is giving to the public what he has learned over so many years. Although it is his intention simply to pass on the words of his predecessors without imposing his own ideas, it is inevitable that, in translating from Chinese to English, the difference in cultural context makes it necessary for him to provide some interpretation. However, his profound understanding of the art makes these interpretations very helpful for the student. His understanding of “chi“, for example, is striking and valuable. In short, this book is a very valuable reference for anyone who cares for this school of boxing.

Preface

I have been learning the art of Taijiquan (also called Shadow Boxing) for sixty years, and I have also been engaged in teaching the art for forty years. With respect to this art of boxing, with its exceptionally profound theory, I always feel that when I am teaching it is hard to know where to begin.

The study of the art of Taijiquan should be based on the Taiji Classics and Treatises. The essentials of practice and attainment have already been completely included without omissions in the Classics and Treatises, which have been handed down for generations; nevertheless, since these works are independent, they are difficult to understand with out doing intensive reading, cross-referencing, and checking. To help those who desire to study this art understand more easily, I have taken the liberty, despite the limitations of my own understanding, of introducing the Classics and Treatises by synthesizing, classification, and organization of main prints into a concise analysis.

The Classics and Treatises used in this book are based on the currently common available texts of the Yang style. They consist of the following:

• Chang San Feng’s Treatise on Taijiquan

• The Treatise on Taijiquan of Wang Tsung Yueh of the Ming Dynasty

• The Inner most Explanation of the Practice of the Thirteen Postures

• The Song of Striking with the Hand

The theory that is necessary to practice Taijiquan is not difficult, but it is very difficult to reach the realm the theory describes. To do this requires careful practice; it is not something that can be attained just by being taught.

The words of the Classics and of the Treatises are not hard to understand, but if one does too much explanation and commentary, it is hard to avoid adding in one’s own ideas, which makes it easy to stray from the original meaning. This book, therefore, adapts the original texts, without inserting extra interpretation. In my view, the kind of categorization and arrangement done in this book is enough to allow the details and specifics to become clear by themselves, and can lead to the clues to the correct methods of practice. Pursuing a high level in this art depends on correctly apprehending the theory and on hard practice. But since it is possible that my own thoughts may not be correct. I hope that my expert readers will take the trouble to correct my errors.

I must acknowledge the encouragement and support of my fellow senior disciple, Mr. William C.C. Chen, in the publication of this book. I also want to thank my old friend, Mr. Ron Koeneoke and Nora Zhu (Mrs. Koeneoke), my follower, Mr. Richard Brzustowicz, Jr. and Mr. Bernard Tony Zayner, and Mr. Andrew Heckert of Philadelphia, who contributed to the checking of the original text and the subsequent translation in English.

The Compiler New York, N.Y. June 10, 1993

A little beneath the surface of the Taiji Quan Classics

1. Goal

What is the standard by which we judge the basis and applications of practices? The correct method is that the mind commands and the body (bone and muscle) obeys.

What is the goal of push hands? Constant youthfulness and a long life.

The original commentary says: These are the transmitted words of the Taoist Patriarch, Chang San Feng of Wu Dang Mountain. He wanted the heroic, greathearted people of the world to have long lives, and never to waste their lives in struggling with less important techniques.

2. Schools

There are many schools of boxing where teaching is oriented toward combat. Although, they all have differences that do not go beyond relying on strength to bully weakness or making the slow yield to the swift. The forceful beat the less forceful, and the slow yield to the swift – Yet this is the result of physical endowment, and not of practical application or experience.

3. Principle

The Taj Ji comes from the Unbounded (Infinity or Wu Chi), and is the source (mother) of Yin and Yang. If it moves, it separates; if it is static, it combines.

4. The Method of Learning

Oral guidance by a competent master, coupled with continual practice, will bring you to a point where the cultivation of skill will take care of itself.

5. Prerequisites

Consciousness

All movements should be directed by consciousness (intention), and not by external appearance. When moving up or down, front or back, left or right, the same intention appears.

Mind

First the mind then the body (when the abdomen is completely relaxed, the Chi can rise in the body spontaneously); then the Chi can penetrate into the bones. When your spirit and body are at ease you can always move as your intention directs.

The mind is in charge

The mind should direct the Chi to move. The Chi should be completely composed. Then it will penetrate to the bones.

Chi

The Chi is the flag. The Chi, circulating freely, mobilizes the body (the Chi is like a cartwheel). If Chi is correctly cultivated, one’s vital spirit will be raised. This eliminates slowness or clumsiness of the body.

Waist

The waist is like a banner (like an axle, like the earth’s axis). Be careful about your waist at all times. The waist is the source of command (the waist dominates).

Sacrifice Ambitions

First sacrifice one’s own ambitions, and follow others, but learn these techniques correctly. The slightest deviation will take you off this path.

Even an error as small as the bending of a single hair can lead one astray a thousand li (one li is about half a kilometer). Students must examine this in careful detail.

Without Excess or Defect

After yielding to pressure from an opponent adhere to him. Then stretch your consciousness toward your opponent and let your action reach him. (After you yield to pressure then bend. Afterward comes extension and reward). The straight comes from bending.

Bending and Extending; Opening and Closing

The movements of bending and extending, of opening and closing, can be automatic (free and spontaneous).

Withdrawing and Adhering

The other is stronger than I am. I need to become soft and yield to the other’s attack. This is called Zou, withdrawing.

My situation is better than my opponent’s (he is more easily controlled). This is called Nien, adhering.

(Speed) Respond quickly to fast actions and slowly to slow actions.

6. Basic Concepts

Form

In practice, begin with larger movements and reduce them to smaller ones. In this way, they will become perfectly compact.

The thirteen postures should never be neglected. You should cherish the specific meaning and then you will know the purpose of each posture. If you carefully examine your postures, you will not feel you are wasting time and energy.

Errors in Practice

It is really a pity if one does not know the purpose and goal of practice! Subsequently, one will waste time and energy.

Push Hands

The purpose of ward-off, roll-back, press and push should be made a subject of careful study. If upward and downward are linked together in the body, there will be no crack through which another can enter.

Let the opponent use immense force against you. Deflect the momentum of a thousand jin (one jin is about 1.1 pounds) using a trigger force of only four ounces. Lead your opponent in. Let your opponent become unbalanced and concentrate your power at that moment .

Adhere (Nien), be continuous (Lien), Stick (Tie), Follow (Shi), and neither pull away nor push back (bu diu, bu ding).

Observe the words “to deflect the momentum of a thousand jin, use a trigger force of four ounces”, which clearly mean not to win the game just by strength.

Watch the form and speed of the old man (of 80 to 90 years) who defends himself from young men. How can he do it so well?

7. Guidelines for the body

The crown of your head should fall as though it was lifted upward, but your neck should only contact your collar lightly. You should feel as if your head were suspended from above by a string.

When your vital spirit is raised you need not worry about clumsiness or slowness.

This is what is called the head being suspended from above by a string.

When the buttocks and spine are held straight, the spirit reaches the top of the head. When the head is held as if suspended by a string from above, the entire body feels light and nimble.

In standing, the body should be erect and relaxed. It should resemble a balance, able to respond immediately to an attack from any of the eight directions. Its activity resembles the wheel of a cart.

8. Requirements for the Postures

(Lightness and nimbleness)

In any movement, the whole body should be light and nimble (agile).

(The entire body should be so light that eventually even the touch of a feather will be noticed, and so responsive that even a fly can not find a firm place to land.)

Linking Together

One should be linked together, with all one’s parts linked like cash (old Chinese coins with a square hole in the middle) strung on acord. Sound boxing is rooted in the feet, develops in the legs, is ruled by the waist, and functions through the fingers. The feet, leg and waist must act as one unit. When this is done in advancing and retreating you can gain the advantage from opportunities provided by your opponent and from your momentum.

Errors in Practice

If you fail to gain from these advantages of opportunity and momentum, your body will be disordered and confused. To correct this, simply adjust your waist and legs.

Chi

The Chi (or momentum) should move like a wave in space.

The Chi sinks (not by force) to the Dan Tien (inside the abdomen below the navel). When the abdomen is completely relaxed, the Chi can rise in the body spontaneously.

Respiration must be natural, so that your movements will be active and alert.

The Chi will then flow without hindrance throughout your body.

The Chi (or momentum) should pass through the body as though easily threaded through the pearl of nine zigzag paths. Then there will be nothing you can not achieve.

If the Chi is cultivated naturally and with a quiet spirit, no harm will come.

The Vital Spirit.

The Vital Spirit should be retained within.

(Combine: Lightness and nimbleness must be linked together with Chi and Spirit).

Do not show either:

• defect or collapse

• concavity or convexity

• severance or splicing

All parts of the body must be threaded together, inch by inch, without any gap or break in continuity.

The power or momentum of Long Boxing (another name for Taj Ji Quan) flows unceasingly like the Yang Tze river or a great surging sea.

Ward-off, Roll-back, Push, Press, Pull, Split, Elbow and Shoulder (the eight postures of Push hands) correspond to the Eight Trigrams of the I Ching.

Advance, Retreat, Look Left, Gaze Right, and Central Equilibrium (the movements) correspond to the Five Elements (of Chinese natural philosophy).

Ward-off, Roll-Back, Press and Push correspond to Jian, Kun, Kan and Li (the four right-angle Trigrams).

Pull, Split, Elbow and Shoulder correspond to Sun, Zhen, Dui and Geng (the four diagonal Trigrams).

Advance, Retreat, Look, Gaze and Central Equilibrium correspond to Metal, Wood, Fire and Earth (the Five Elements).

When combined, these five steps and eight postures make up the original thirteen T’ai Ji Quan postures.

9. Insubstantial and Substantial

The change from insubstantial to substantial and back should be done carefully.

Mind (consciousness) and Chi (or momentum) should be exchanged sensitively. This is very satisfying . This is called mutual interchange or exchange of insubstantial and substantial.

Insubstantial and substantial must be clearly differentiated. Every boxing experience, at any given time, has substantial and insubstantial aspects. In boxing, it is the entire body that has this feature of being insubstantial or substantial.

Although situations change like a kaleidoscope, the principles remain the same.

10. Techniques (Push hand & Application)

When something happens above, one must pay attention below. When something happens in front, one must pay attention behind. When something happens on the left, one must pay attention to the right. If one intends to move up, one must simultaneously travel downward, as when pulling up a tree one moves the roots first in the other (reverse) direction, and is thus able to uproot it immediately.

11. Hearing Momentum

Do not incline to either side or lean forward or back (postures must be done erectly). The truth of the postures should be suddenly hidden, or suddenly revealed.

When the opponent brings pressure on your left side, that side should be insubstantial (empty). When pressure is put on your right side, that side should vanish.

If the opponent is aspiring to move upward, you should follow by being higher. If the opponent desires to move downward, you should follow by being deeper. An opponent seeking to advance should feel that the distance between you is becoming incredibly long. A retreating opponent should feel that the distance is exasperatingly short.

If your opponent does not move, you should not move. Your motion should predict your opponent’s slightest move. You arrive at his destination first.

The Ideal

Even a feather cannot be added to, nor can a fly alight on the body. The other person does not know me at all, but I know him very well. Why is the hero always unmatched everywhere? For this reason only.

When energy is apparently loose but not actually loose, it is about to unfold but has not yet unfolded. Even if your energy is broken, you should not let your intention be broken.

Drawing in is liberation (release). If energy breaks, it can be connected again.

Keep your body sunk, and weighted on one side. Then your momentum will flow continuously. Otherwise, if your weight spreads on both sides, your body is double-weighted, and you will move sluggishly.

Error in Practice

If one has practiced T’ai Ji Quan hard for many years but has never learned the preceding points well, one will still be controlled by others. All because one has still not recognized the error of being double – weighted.

In order to avoid this mistake, understand the regulation between Yin and Yang (their mutual relationship).

This is called understanding the momentum of the postures.

To develop skill in striking, gradually understand the momentum of the postures; then you will go on to achieve miraculous effects. You must practice for a long time. You cannot expect to achieve everything immediately.

To understand the momentum of postures, the more you practice the better will be your skill. Silently and internally fathom the distinctions. Follow your way step by step.

12. Energy momentum

Mobilize your energy (momentum) as if pulling silken thread from a silkworm’s cocoon (continuously).

The energy will be purified like steel that has been refined a hundred times.

From the most pliable and yielding, you will become the most powerful and unyielding, allowing any object to be destroyed.

Energy should be reserved so that you have some to spare (do not exhaust it completely). Before attacking, you should first draw in your energy.

Reserving or storing energy is like pulling a bowstring. Releasing it is like shooting an arrow.

Releasing energy should be sunk deeply. Relax completely and aim in a single direction.

As you move and go, the Chi should adhere to your back and gather into the spine. Inwardly, concentrate your spirit. Outwardly, appear quiet and peaceful.

Energy is developed from the spine. Your steps must be altered in accordance with the position of your body. Walk like a cat.

When movements exchange back and forth, use the technique of folding up (this technique uses the all joints of the body). Postures should be exchanged in advancing and retreating.

Act like a hawk seizing a rabbit, or copy the spirit of a cat watching a rat.

When an opponent touches my motionless body, though it causes motion, I am still at ease. My reactions to an opponents changes are wonderful and surprising.

Remember, as soon as you move at all every part must be moving. As soon as you stop there should be no part that has not stopped.

When the form (Chi and momentum) is still, it is like a mountain. When it moves, power flows unceasingly like a long river or great surging sea.

Pay great attention to the spirit of the whole body. Do not pay any special attention to your Chi or respiration; otherwise, your actions will be weakened and clumsy.

If you pay attention to your Chi (respiration) you will have no energy; if you do not force your Chi, your energy will be strong and hard.

Recommended reading on Taijiquan Classics

German Translation of the Taijiquan Classics

T’AI CHI CH’UAN CLASSICS researched by Lee N. Scheele

Author: Ping-Siang Tao

Images: Nils Klug