FENCING PROCESS

Disengagements in order to cut are of two kinds, one with the O’s energy, and one against it.

In the first instance, if the O’s blade is pressing on ours, we should continue letting our blade move in that direction until, at the right time, we disengage, circle back and cut. This is usually a light to medium cut.

In the second case, if the O is pressing strongly on our blade we should use the O’s pressure to allow our blade to circumvent, or slip past their blade, in an action similar to snapping our fingers. This is a dramatic but risky move, since, for an instant, our sword position ‘matches’ the O’s. When our point is near their point and our pommel is near their pommel, there is an opportunity for the O to contact our pommel with his left hand. As we execute this move we must move past them to reconnect defensively with our left hand. There is a lot of energy generated when the O is pressing hard and we must be careful to make our sword hand extremely yin as we cut to avoid injury.

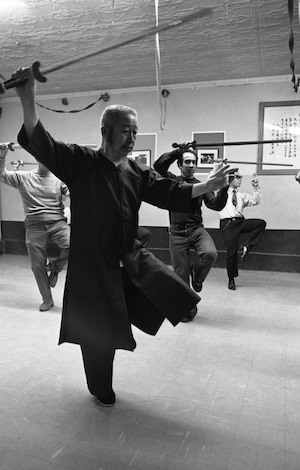

In the Shr Jung School Professor Cheng taught us to start off each fencing match with a wide swinging horizontal cut (like “Block and Sweep” in the form) in order to acquaint ourselves with the difficulty and necessity of joining and sticking with a fast incoming blade.

I am very often confronted with fencers who ignore or disrespect the O’s sharp edge and abandon their defensive contact by disengaging in order to cut. This action leaves them vulnerable, a mistake that often results in both parties getting cut (10,000 sword faeries will laugh at them).

It is the highest level to cut or thrust while maintaining defensive contact. It is always dangerous to disengage, but occasionally it is demanded, or at least strongly invited by the O.

Many will disengage and cut to the wrist or forearm with speed and strength in order to win. We may disengage and cut if we feel that the O is asleep or is entertaining a thought. If and when we do it, we must either re-establish defensive contact with our left hand as we cut, or move by backing away, or passing by the O. Either of these movements creates added benefit, providing us with a more effective cut, as the blade slices, when it moves along its length. We should only cut with speed if the O has given us the energy to do so. If we disengage without the O putting pressure on our blade, we are ‘doing something’. The O may then cut us in response, by filling the vacuum we have created. When we disengage as a result of the O’s pressure, he has done something and we are using his action. This is according to the principle of “Wu Wei” (non action).

There exists a conundrum while fencing, as in all aspects of Tai Chi, we must be relaxed “Yin”. In addition, as we make grand sweeping cuts we are told to completely relax our wrists, so as not to injure our partners. If we were in an actual duel we would, on the contrary, become extremely “Yang” at that moment of contact, in order for the cut to be effective. The answer is found in the Taoist axiom “Extreme Yin becomes Yang, and extreme Yang becomes Yin” . So if we needed to go from protecting our partners to cutting an attacker, it would be a small leap of energy differentiation.

It is of benefit from time to time to close the eyes, so as not to depend on them for energy interpretation. In the beginning practise it slowly, without moving the feet whilst trying to stay in defensive contact. Cut only while in contact, and without thrusting.

When we are fencing with the O’s blade on the right side of our blade our sword arm should have a rounded shape from the shoulder through the sword. If the right wrist is bent and our right elbow sticks out it will present an easy target. Beginners frequently make this mistake.

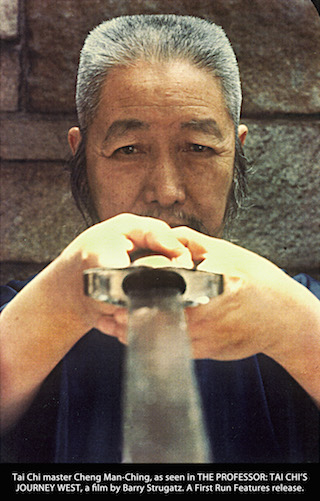

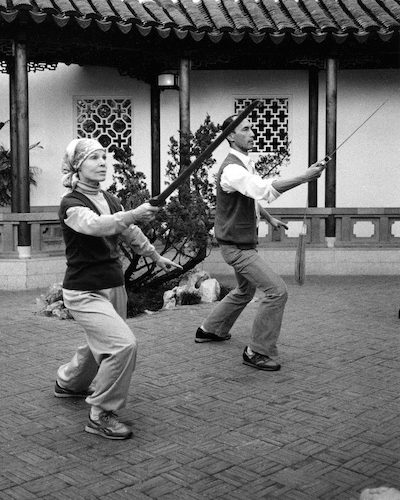

Author and Images: Ken van Sickle

German version on our sister site!

- ON BEING A MASTER – Tai Chi Sword 53

- STRANGERS – Tai Chi Sword 52

- PADDED SWORDS – Tai Chi Sword 51

- SAFETY – Tai Chi Sword 50

- PARALLELS – Tai Chi Sword 49

- Swordsmanship – SEVEN QUOTES – Tai Chi Sword 48

- TI FENG & FA JING – Tai Chi Sword 47

- SUPPOSITIONS – Tai Chi Sword 46

- LAO TZU (Laozi) QUOTES – Tai Chi Sword 45

- ETIQUETTE – Tai Chi Sword 44

- FENCING PROCESS – Tai Chi Sword 43

- STRATEGIES – Tai Chi Sword 42

- TASSELS IN THE WIND – Tai Chi Sword 41

- SHOOT FLYING GOOSE – Tai Chi Sword 40

- RHINOCEROS GAZES AT MOON – Tai Chi Sword 39

- THE MASTER SITS BACK – Tai Chi Sword 38

- FIVE APPLICATIONS – 1. BLOCK AND SWEEP – Tai Chi Sword 37

- RULES OF ENGAGEMENT – Tai Chi Sword 36

- CONSIDER – Tai Chi Sword 35

- INVITATIONS – Tai Chi Sword 34

- THE TASSEL – Tai Chi Sword 33

- THE SWORD FINGERS – Tai Chi Sword 32

- Cheng Man Ching Photographs

- THE JOINTS – Tai Chi Sword 31

- THE GRIP – Tai Chi Sword 30

- SWORD MOVEMENT – Tai Chi Sword 29

- ON ALIGNMENT – Tai Chi Sword 28

- CONCERNING THE CENTRE – Tai Chi Sword 27

- EQUATIONS – Tai Chi Sword 26

- HSIN AND CHI – Tai Chi Sword 25

- On studying – NINE QUOTES – Tai Chi Sword 24

- THE SWORD MAIDENS – Tai Chi Sword 23

- THE SWORD AND CALLIGRAPHY – Tai Chi Sword 22

- Returning – MORE THOUGHTS – Tai Chi Sword 21

- Levels of TAI CHI SWORD – Tai Chi Sword 20

- FENCING – Tai Chi Sword 19

- Transcendence – Tai Chi Sword 18

- TURNING TRICKS – Tai Chi Sword 17

- Names of CHENG MAN CH’ING’S TAI CHI SWORD – Tai Chi Sword 16

- FORCE – Tai Chi Sword 15

- DIFFERENCES – Tai Chi Sword 14

- BEGINNERS’ MISTAKES – Tai Chi Sword 13

- MIND SETS – Tai Chi Sword 12

- SENSITIVITY – Tai Chi Sword 11

- HARMONY – Tai Chi Sword 10

- TIME AND HUMOUR – Tai Chi Sword 9

- WHY AND HOW – Tai Chi Sword 8

- SWORD DIMENSIONS – Tai Chi Sword 7

- A ROYALTY OF ARMS – Tai Chi Sword 6

- KENNETH VAN SICKLE – Tai Chi Sword 4

- CHENG MAN CH’ING – Tai Chi Sword 5

- PREFACE – Tai Chi Sword 3

- Introductory Thoughts – Tai Chi Sword 2

- EDITOR’S PREFACE -Tai Chi Sword 1

- Tai Chi Sword by Kenneth van Sickle