SWORD AND CALLIGRAPHY

In China calligraphy is as esteemed as painting. Calligraphers are recognized and venerated and their work receives critical acclaim or disdain. It is bought for prices rivalling that of paintings and is collected by connoisseurs.

Long ago when China was a meritocracy the emperors courted the favour of the royalty and cultural elite, encouraging mastery of the art and furthering it as one of the supreme excellences.

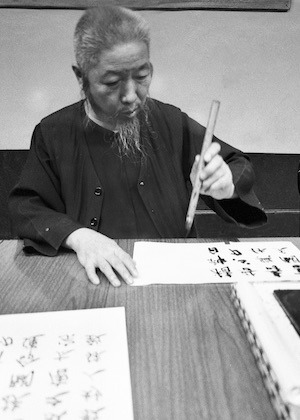

The more than 40,000 characters in the Mandarin ‘alphabet’ began with a few simple strokes, which are called ‘radicals’ to represent ‘things’, each one looking like the object it portrayed. These characters are depictions, not abstract symbols, as with most languages. As time passed the characters changed, resembling the original objects less and less. However, it is studied starting with the original style and going through all the steps of its evolution. In this manner the students retain the essence of the original ‘picture’.

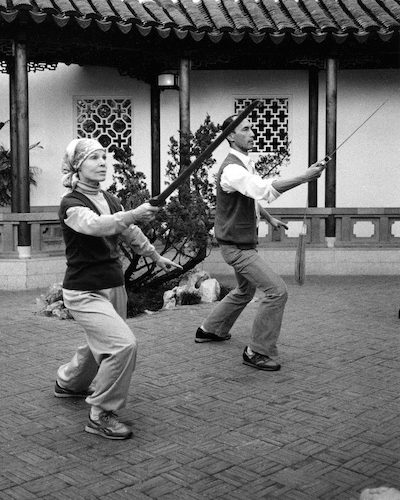

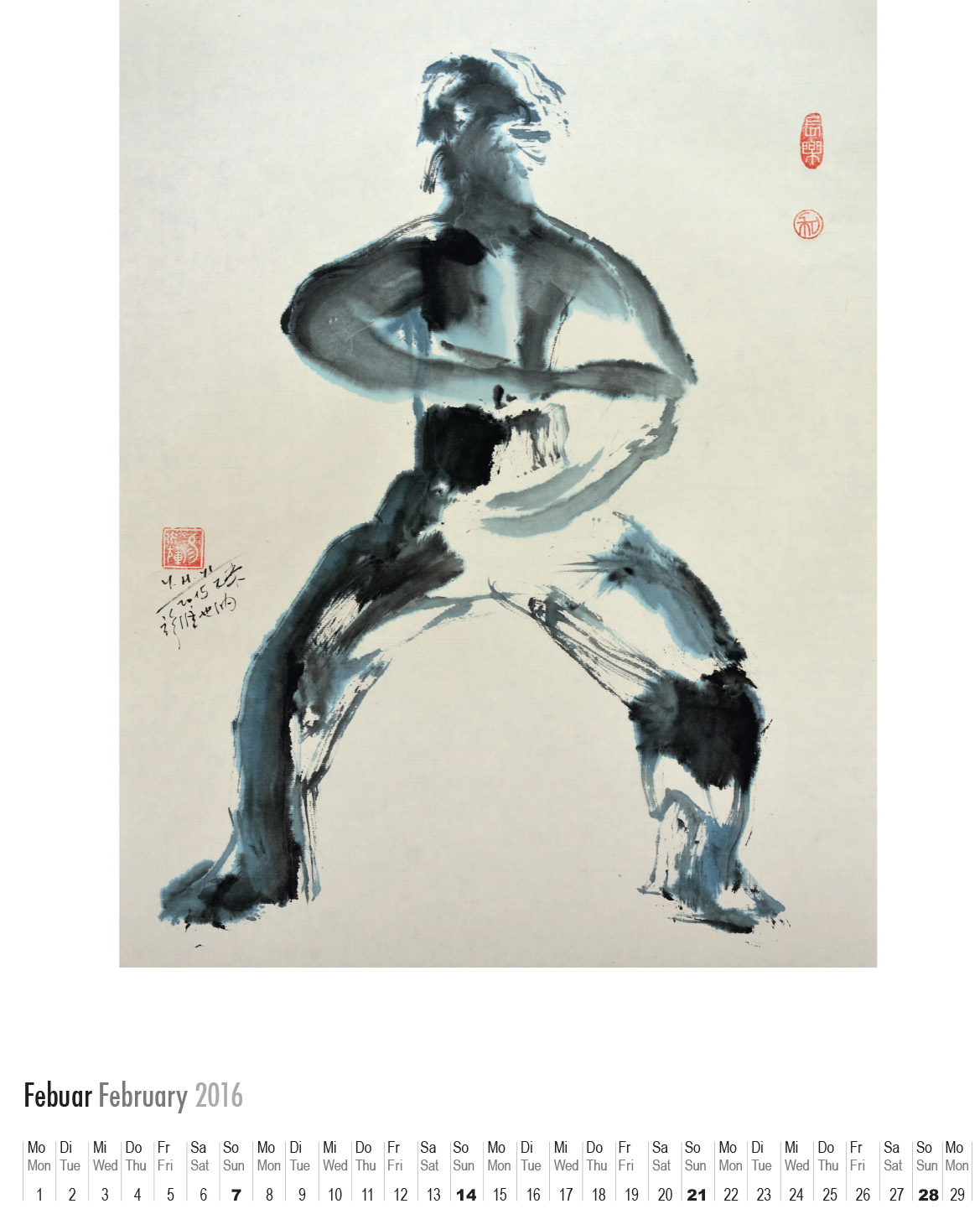

Calligraphy and fencing are considered companion arts in China, the skills of one enhancing the skills of the other. Frequently a calligrapher will illustrate the correct energy and movement for the brush by displaying a sword movement, and vice versa.

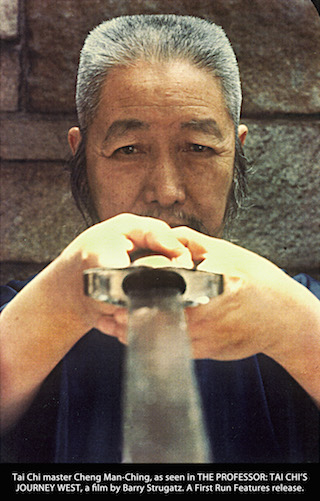

Occasionally, Cheng Man Ch’ing would lightly pull a student’s brush upward as they were executing a stroke. If they were holding the brush too tightly it would mess up the character they were making, and if it were too loose the brush would slip out of their grasp, leaving black stains on their fingers. If they were holding the brush correctly their hand would simply rise with the brush, again similar to sword principle.

Cheng Man Ch’ing said that one who learns and communicates through a language that depicts, develops a different kind of mind than one who learns a language that uses abstract figures.

Author and Images: Ken van Sickle

German version on our sister site!

German version of this article

- ON BEING A MASTER – Tai Chi Sword 53

- STRANGERS – Tai Chi Sword 52

- PADDED SWORDS – Tai Chi Sword 51

- SAFETY – Tai Chi Sword 50

- PARALLELS – Tai Chi Sword 49

- Swordsmanship – SEVEN QUOTES – Tai Chi Sword 48

- TI FENG & FA JING – Tai Chi Sword 47

- SUPPOSITIONS – Tai Chi Sword 46

- LAO TZU (Laozi) QUOTES – Tai Chi Sword 45

- ETIQUETTE – Tai Chi Sword 44

- FENCING PROCESS – Tai Chi Sword 43

- STRATEGIES – Tai Chi Sword 42

- TASSELS IN THE WIND – Tai Chi Sword 41

- SHOOT FLYING GOOSE – Tai Chi Sword 40

- RHINOCEROS GAZES AT MOON – Tai Chi Sword 39

- THE MASTER SITS BACK – Tai Chi Sword 38

- FIVE APPLICATIONS – 1. BLOCK AND SWEEP – Tai Chi Sword 37

- RULES OF ENGAGEMENT – Tai Chi Sword 36

- CONSIDER – Tai Chi Sword 35

- INVITATIONS – Tai Chi Sword 34

- THE TASSEL – Tai Chi Sword 33

- THE SWORD FINGERS – Tai Chi Sword 32

- Cheng Man Ching Photographs

- THE JOINTS – Tai Chi Sword 31

- THE GRIP – Tai Chi Sword 30

- SWORD MOVEMENT – Tai Chi Sword 29

- ON ALIGNMENT – Tai Chi Sword 28

- CONCERNING THE CENTRE – Tai Chi Sword 27

- EQUATIONS – Tai Chi Sword 26

- HSIN AND CHI – Tai Chi Sword 25

- On studying – NINE QUOTES – Tai Chi Sword 24

- THE SWORD MAIDENS – Tai Chi Sword 23

- THE SWORD AND CALLIGRAPHY – Tai Chi Sword 22

- Returning – MORE THOUGHTS – Tai Chi Sword 21

- Levels of TAI CHI SWORD – Tai Chi Sword 20

- FENCING – Tai Chi Sword 19

- Transcendence – Tai Chi Sword 18

- TURNING TRICKS – Tai Chi Sword 17

- Names of CHENG MAN CH’ING’S TAI CHI SWORD – Tai Chi Sword 16

- FORCE – Tai Chi Sword 15

- DIFFERENCES – Tai Chi Sword 14

- BEGINNERS’ MISTAKES – Tai Chi Sword 13

- MIND SETS – Tai Chi Sword 12

- SENSITIVITY – Tai Chi Sword 11

- HARMONY – Tai Chi Sword 10

- TIME AND HUMOUR – Tai Chi Sword 9

- WHY AND HOW – Tai Chi Sword 8

- SWORD DIMENSIONS – Tai Chi Sword 7

- A ROYALTY OF ARMS – Tai Chi Sword 6

- KENNETH VAN SICKLE – Tai Chi Sword 4

- CHENG MAN CH’ING – Tai Chi Sword 5

- PREFACE – Tai Chi Sword 3

- Introductory Thoughts – Tai Chi Sword 2

- EDITOR’S PREFACE -Tai Chi Sword 1

- Tai Chi Sword by Kenneth van Sickle